|

The Troyer Interview

Sunday, March 15, 2015 | Movies & TV

This interview was conducted by writer/TV host Warner Troyer in March 1977 on behalf of the Ontario Educational Communications Authority. It was broadcast on TVOntario, a public television network which had shown The Prisoner series along with commentaries from Troyer between October 1976 and February 1977.

You need Flash to navigate this site.

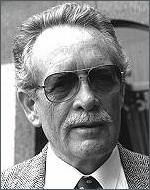

Troyer: I guess the first thing I should tell you is that your guest and mine is Patrick McGoohan. Mr. McGoohan, known familiarly to his friends as Number Six, was the creative force behind, the executive producer of, and in several cases the script writer of a series called "The Prisoner," which appeared on television a number of times, not least notably on this network. Mr. McGoohan has come here from Los Angeles to meet you and talk to you and to me. And to meet a group of Prisoner, ah, club groupies, some of them from Seneca College which has been operating a course based on the series, some of them from OECA, and some other people, and we're going to talk about "The Prisoner" and I suppose the obvious first question is: Where the hell did that idea come from? How'd you get started?

McGoohan: Boredom, was how it started.

Troyer: Just that? With T.V.? With society, or you?

McGoohan: With T.V. initially. I was doing a series that was called "Secret Agent." Was it called that here, or "Danger Man"? It had two titles.

Troyer: "Danger Man."

McGoohan: And I'd made 54 of those and I thought that was an adequate amount. So I went to the gentleman, Lew Grade, who was the financier, and said that I'd like to cease making "Secret Agent" and do something else. So he didn't like that idea. He'd prefer that I'd gone on forever doing it. But anyway, I said I was going to quit. So he said, "What's the idea?" This is on the telephone initially, so I met him on a Saturday morning at 7 o'clock. That was always the time we had our discussions, and he said "Alright, what's the idea?" and I had a whole format prepared of this "Prisoner" thing which initially came to me on one of the locations on "Secret Agent" when we went to this place called Portmeirion, where a great deal of it was shot, and I thought it was an extraordinary place, architecturally and atmospherewise, and should be used for something and that was two years before the concept came to me. So I prepared it and went in to see Lew Grade. I had photographs of the Village or whatever and a format and he said, "I don't want to read the format," because he says he doesn't read formats, he says he can't read apart from accounts, and he sort of said, "Well, what's it about? Tell me." So I talked for ten minutes and he stopped me and said, "I don't understand one word you're talking about, but how much is it going to be?" So I had a budget with me, oddly enough, and I told him how much and he says, "When can you start?" I said Monday, on scripts. And he says, "The money'll be in your company's account on Monday morning." Which it was, and that's how we started. Behind it, of course, was a certain impatience with the numerology of society and the way we're being made into ciphers, so there was something else behind it.

Troyer: Was that a personal thing in terms of your reaction to society or was it more of an observation? Do you feel you're being...

McGoohan: I think we're progressing too fast. I think that we should pull back and consolidate the things that we've discovered.

Troyer: You didn't initially want to do 17 films?

McGoohan: No, seven, as a serial as opposed to a series. I thought the concept of the thing would sustain for only 7, but then Lew Grade wanted to make his sale to CBS, I believe (first ran it in the States) and he said he couldn't make a deal unless he had more, and he wanted 26, and I couldn't conceive of 26 stories, because it would be spreading it very thin, but we did manage, over a week-end, with my writers, to cook up ten more outlines, and eventually we did 17, but it should be 7.

Troyer: But you did ten in two days? Ten outlines?

McGoohan: Over a week-end, yes. Outlines, I mean a sort of...7 or 8 page format. (Troyer chuckles.)

Troyer: How would you have described or explained the concept of the series to those writers, the first time you sat down with them, what did you tell them?

McGoohan: It was very difficult because they were also prisoners of conditioning, and they were used to writing for "The Saint" series of the "Secret Agent" series and it was very difficult to explain, and we lost a few by the wayside. I had sat down and I wrote a 40-page, sort of, history of the Village, the sort of telephones they used, the sewerage system, what they ate, the transport, the boundaries, a description of the Village, every aspect of it; and they were all given copies of this and then, naturally, we talked to them about it, sent them away and hoped they would come up with an idea that was feasible.

Troyer: What about the philosophy, the rationale of the Village? What did you tell them about that? Its raison-d'etre, not its mechanics...

McGoohan: (very deliberately) It was a place that is trying to destroy the individual by every means possible; trying to break his spirit, so that he accepts that he is No. 6 and will live there happily as No. 6 for ever after. And this is the one rebel that they can't break.

Troyer: To what end was that process of breaking down the individual will?

McGoohan: To what end?

Troyer: For the Village, what was the purpose, the goal?

McGoohan: I think it's going on every day all around us. I had to sign in to get into this joint! (Troyer: Uh-huh) Downstairs, yeah.

Troyer: Made you angry, too? (Chuckle.)

McGoohan: Slightly, yeah. Pass-keys and, you know, let's go down to the basement and all this. That's Prisonership as far as I'm concerned,and that makes me mad! And that makes me rebel! And that's what the Prisoner was doing, was rebelling against that type of thing!

Troyer: But can you, in everyday life, summon the will and the energy to rebel every time any indignity occurs?

McGoohan: You can't, otherwise you go crazy! You have to live with it. That's what makes us prisoners! You can't totally rebel, otherwise you have to go live on your own, on a desert island. It's as simple as that.

Troyer: How much psychic attrition is there, spiritual attrition in not rebelling? How much do you give away or lose? How high is the cost of not rebelling every time? Not complaining every time?

McGoohan: Ulcers, ulcers.

Troyer: Do you have ulcers?

McGoohan: I have a couple.

Troyer: Bad ones?

McGoohan: Not too bad. They're gettin' worse. (laughs)

Troyer: How many scripts did you write? Your name was on two.

McGoohan: Well, my name was on two and then I wrote under a couple of other names: Archibald Schwartz was one and Paddy Fitz was another.

Troyer: So how many all together?

McGoohan: I t'ink five.

Troyer: Which ones? The last one...

McGoohan: The first one I re-wrote. It came out...not the way I wanted, and then the last one, I wrote. The penultimate one, I wrote. Free For All - another one, and then there was another one, I can't remember the name of it offhand. It's a long time ago.

Troyer: What's your response to what could really only be adequately described as a "cult" which has grown up around the series, a kind of mystique about it, here and in Europe?

McGoohan: I'm very gratified because, when it came out originally, in England, there were a lot of haters of it. A love/hate relationship, whichever way you look at it. Already there was a small cult. Now there's a much bigger one over there. In fact, when the last episode came out in England, it had one of the largest viewing audiences, they tell me, ever over there, because everyone wanted to know who No. 1 was, because they thought it would be a "James Bond" type of No. 1. When they did finally see it, there was a near-riot and I was going to be lynched. And I had to go into hiding in the mountains for two weeks, until things calmed down. That's really true!

Troyer: They were angry?

McGoohan: Oh, yeah! Walking around the streets, it was dangerous!

Troyer: Why? Why were they angry?

McGoohan: Because they thought they'd been cheated. Because it wasn't, you know, a "James Bond" No. 1 guy.

Troyer: It was themselves.

McGoohan: Yes, well, we'll get into that later, I think. (Knowing laughter from Troyer) Come back to that one, that's a very important one.

Troyer: D'ya know what's really interesting, to me, is a number of my friends and colleagues who watched the entire series told me, after the last show, that they were angry because they hadn't found out who No. 1 was. That went by quickly and they refused to acknowledge it.

McGoohan: That was deliberate. I forgot how many frames; I think there were 52 frames, or something, of the shot when they pulled off the monkey mask. And No. 1's a monkey and then No.1's himself. It was deliberate. I mean, I could have held it there for a good two minutes and put a subtitle on it saying, "It's him," you know. (All laugh.) But I thought I wasn't going to pander to a mentality so low that it couldn't perceive what I was trying to say, so you had to be a little quick to pick it up. That's all.

Troyer: What is your response to all the analysis and all the philosophising and criticism of the series? People have tried to make *so* much of it and to find so many levels of meaning, to parse it in so many directions.

McGoohan: I'm astonished! For instance, the beautiful presentation, the thing that you prepared for our good friends here, puts profounder meaning into many of the stories than I ever thought of.

Troyer: (Chuckling) Or more pompous?

McGoohan: (Automatically) Yeah. (Troyer chuckles again.) No! Oh, no, not at all. No, no. I think it's marvelous; I'm most gratified.

Troyer: Some questions...over here...

Girl: How did you feel about the response to "The Prisoner" when it was first shown in Britain?

McGoohan: Delighted. I wanted to have controversy, argument, fights, discussions, people in anger waving first in my face saying, "How dare you? Why don't you do more 'Secret Agents' that we can understand?" I was delighted with that reaction. I think it's a very good one. That was the intention of the exercise.

Troyer: Did you get any special kind of response from politicians, from bureaucrats, people in the kind of corporations we all know and hate?

McGoohan: Not enough. I suppose they steered clear of it. But then, of course, they'd be the very ones that wouldn't understand it.

Troyer: Uh-huh. Was there any one that was more fun for you than the other? Was it fun playing a Western?...a western hero for a few scenes?

McGoohan: I don't know what concepts you good folks have put on that one, but the reason for that, I'll tell ya, is because I wanted to do a Western. I'd never done one. And they'd never made a Western in England, and we were short of a story. (All laugh.) So we cooked that one up, we wrote it in four days and shot it, ya know...

Troyer: It was harmless...

McGoohan: it was fun, yeah, it was fun. And takin' whatever you put into it, that's the reason for it. Then we sorta stuck the figures up and all that and put some other concepts in which have other levels, sociological levels, which you can take what you want out of them.

Troyer: Can you make a decent creative enterprise, build one, in any medium, without building it on several levels at once? However much of it is conscious or unconscious?

McGoohan: It's very, ah...a lot of it was conscious, in my case. Of course, other things happen. F'instance, a t'ing happened, the balloon thing, which has been made a great deal of...

Troyer: "Rover."

McGoohan: "Rover," yes. Now, the reason that happened, again, it's like the Western. This, ah...We had this marvelous piece of machinery that was being built which was gonna be "Rover" and this thing was like a hovercraft and it would go underwater, come up on the beach, climb walls; it could do anything. The was our original Rover.

By the first day of shooting, unfortunately, the engineers, mechanics and scientific genuises hadn't quite completed it to perfection. (Troyer chuckles.) And the first day of shooting, Rover was supposed to go down off the beach into the water, do a couple of signals and a couple of wheelspins and come back up. But it went down into the water and (laughter all around) stayed down, permanently.

And then we had to shoot. We had Rover in every scene that day. So we had no Rover and Rover didn't look as though he was going to be resurrected at all. So we're Free For Allstanding there. My production manager, Bernard Williams (wonderful fellow), standing beside me, and he says, "What're we gonna do?" And he went like that and he looked up and there was this balloon in the sky. And he says, "What's that?" And I said, "I dunno. What is it?" He says, "I think it's a meteorological balloon." And he looked at me. And I said, "How many can ya get within two hours?", ya see. So he says, "I'll see." And he went off and he called the meteorological station nearby. And I did some other shots to cover while he was away and he came back with a hundred of 'em. He took an ambulance so that he could get there and back fast because it was quite a ways to the nearest big town. And he came back with them and there were these funny balloons, all sizes, and that's how Rover came to be.

And sometimes we filled it with a little water, sometimes with oxygen, sometimes with helium, depending on what we wanted him to do. And in the end, we could make him do anything: lie down, beg, anything (Laughter)...Really. We used about six thousand of them...

Troyer: Did you really?

McGoohan: Oh, yes. They're very, very fragile. They break very easily.

Troyer: So you'd lose a lot of scenes, then, when you were shooting in a boat...

McGoohan: We always had another one standing by, back-ups, all the time, yes.

Boy: What interested me was the style in which it was done and the whimsy and the hundreds of little touches, but from what you've been saying so far, they all seem to have been accidents. You know, the white balloon was a accident and you happened upon the Village...

McGoohan: Oh, yeah...

Boy: And it's, you know, incredibly lucky.

McGoohan: Yeah, but you...no, no, no, no...There were these pages, don't forget, at the very beginning, which laid out the whole concept; these forty-odd pages laid out the whole concept. That was no accident.

Boy: No, but the little touches...

McGoohan: Those things come anyway.

Boy: But I haven't seen them come very often in any other series.

McGoohan: But they come because you're looking for them, you see. I was fortunate to have two or three creative people working with me, like my friend that I said saw the meteorological balloon. And wherever one could find these little touched, one put them in. But the design of the "Prisoner" thing, that was all clearly laid out from the outset.

Boy: And the style of the way...

McGoohan: And the style was also clearly laid out and the designs of the sets, those were all clearly laid out from the inception of it. There was no accident in that area, you know, the blazers, and the numbers and all that stuff, and the stupid little bicycles and all that.

Troyer: Was it a series, do you think, which had an appeal, a kind of narrow-gauge appeal, chiefly to people in the upper twenty percent of the intelligence quotient bracket or whatever?

McGoohan: Mostly intelligent people...such as we have here?

Troyer: Yeah, I meant that.

McGoohan: You see, one of the t'ings that is frustrating about making a piece of entertainment is trying to make it appeal to everybody. I think this is fatal. I don't think you can do that. It's done a great deal, you know. We have our horror movies and we have our science-fiction things. The best works are those that say...somebody says, "We want to do something this way," and do it, not because they're aiming at a particular audience. They're doing it because it's a story they think is important, and is a statement that they want to make. And they do it and then whoever want to watch it, that's their privilege. I mean, the painting in an art gallery, you know, you have a choice whether you go and look at this one or that one or the other one. You have a choice not even to go in.

Second Boy: One analogy that comes up, from literature, is with epic poetry, or with an epic. And "The Prisoner" seems to have all the qualities that belong to an epic, including the kind of structure which you ended up with: the thing that began with seven parts and ended with seventeen.

McGoohan: Yeah.

Second Boy: There have been a few peculiar epic works which have done that sort of thing or been on the way, Spencer's "Faerie Queene" for instance, or Tennyson's "Idylls of the Kings" ..."Idylls of the King" which became a twelve-part non-epic with all the properties and qualities of an epic. I have one question based on that perhaps peculiar observation, and that is: one of the figures in some of the epics, like the "Faerie Queene," is the dwarf who accompanies Una and the Redcrosse Knight where the idea for Angelo Muscat come from?

McGoohan: Oh. I don't know. Where did that come from?

Second Boy: Is there a literary image...

McGoohan: No, I certainly never thought of one. There were all sorts of interpretations to little Angelo. He's a very sweet man and...a very, very sweet man. It's this sort of...there should be something also--sinister about him. I mean, there was always the possibility that he might be No. 1. See, I don't know if anyone...do you pick up that at all? I don't know, but that...because he was such a good friend and always by the side of No. 6, that there was...should have been an implication that perhaps he was a sinister character, and particularly in the last episode, when he goes...he's the one that goes out with No. 6 and they go into the...Maybe he's over No. 1 somewhere...you know they have so...they have stars, superstars, and what are they gonna call them next? Comets? So what...maybe he's a comet or something, little...little Angelo. So there should be that remaining sinister thing about it.

Second Boy: I was just curious, because there were so many images of all...of all the figures that are in the series that are...that have literary connections, whether of not they're deliberate...(McGoohan: Yeah.)...deliberately connected or not doesn't really matter, does it? There might be an element...

McGoohan: No, I don't think...I don't think it does.

Second Boy: No, doesn't matter at all.

McGoohan: I don't think, in that sort of...I, I use the work "surrealistic" about it...thing, that one has to tie up all the loose ends. I think there's...that you...options are open for the beholder to interpret whichever way he likes.

Third Boy: Mr. McGoohan, my question deals with religion.

McGoohan: Yeah.

Third Boy: I understand, in reading a little about you, that you're a very religious man, and my question pertains to "Fall Out." I have interpreted a lot of the acts as being...having this content. I'm thinking specifically of the crucifixion of the two rebels, of when their arms are drawn apart, the temptation of No. 6 by the President of the Village, of the temptation of Christ...

McGoohan: They give him the throne.

Third Boy: "Drybones," all of that. First of all, would you agree with my idea that that is intentional? That it is...

McGoohan: Ah, answering: No, I had never any religious inspiration for that whatsoever. I was just trying to make it dramatically feasible. Certainly the temptation with the guy putting me up on the throne and all this stuff, ah...it's Lucifer time. But I never thought at that moment. Maybe somewhere in the back of my mind it was there, "And the hip bone's connected to the thigh bone" thing. I just thought it was a very good song for the situation and also was applicable to the young man because, as you know, it's easy for us to go astray in youth and he was astray and he's trying to get everything together again.

Third Boy: When I speak of religion, I mean a moral attitude towards life.

McGoohan: I would think that's necessary, yeah.

Third Boy: OK, then, is it fair to say that No. 6 draws upon that? Is that the source of his defense? Is that how he gets up in the morning and faces another day in the Village?

McGoohan: I think that's a very good comment and I think that's probably true, yeah...moral force which says, "I have a spirit of my own, a soul of my own and it's not all my own because it's joined with a greater force beyond me." I don't think he got up every morning and analyzed it to that extent, but I think that that force is within him and anyone who is able to fight in that individual way.

Third Boy: Would you say that there is a distinct lack in the rest of the villagers? Are they soulless beings?

McGoohan: Ah, the majority of them have been sort of brain- washed. Their souls have been brainwashed out of them. Watching too many commercials is what happened to them.

Troyer: I used to think that television commercials were spiritually healthy because they made us skeptical and that that was probably a very good thing to learn very early on.

McGoohan: Well, they don't make enough people skeptical because if they made enough people skeptical, the people who were made skeptical wouldn't be buying all the junk that they're advertising and then they'd be out of business.

Fourth Boy: There's one sequence you do with Leo McKern where he says, "I'll kill you." You say, "I'll die," and he says, "You're dead." Is that a figure of speech or was there an underlying thing happening there?

McGoohan: Now you're talking about 'Once Upon A Time'?

Fourth Boy: Yeah, 'Once Upon a Time'.

McGoohan: Well, that was very interesting that one...(which was probably my favourite earlier on, Warner. That was probably it.) That was one that was written in the 36 hour period. And Leo McKern, who was a very good friend of mine and a very fine actor I think, came in on short notice to do it, and it was mainly a two hander. The brainwashing thing, he was trying to brainwash me and in the end No. 6 turns the tables. And the dialogue was very peculiar because all it consisted of was mainly "Six, Six, Six," and five pages of that at one time. And Leo, one lunchtime, went up to his dressing room and I went to see the rushes and I knew he was tired. I went up to the dressing room to tell him how good I thought he'd been in the rushes. And he was curled up in the fetus position on his couch there, and he says, "Go away! Go away you bastard! I don't want to see you again." I said, "What are you talking about?" He says, "I've just ordered two doctors," he says, "and they're comin' over as soon as they can." He says, "Go away." And he had. He'd ordered two doctors and they come over that afternoon and he didn't work for 3 days. He's gone! He'd cracked, which was very interesting. He'd truly cracked. And so I had to use a double, the back of a guy's head for a lot and eventually Leo did come back and we completed them and also he was in the final episode, so he forgave me for everything, but he did crack, very interesting, I thought....

Troyer: Much as he cracked in that final episode.

McGoohan: Same, exactly the same.

Troyer: I was wondering about how much intensity there was in that. I know that acting is always an enormously intense experience but in that head-on two hander where there was so much dynamic pressure. Obviously, it was real.

McGoohan: It was 8 days shooting and for most of those 8 days we were head to head on from 8 o'clock in the morning 'til 6:30 at night with an hour for lunch. So, it was pretty intense. It was psychiatrist couch time, sort of thing.

Troyer: Were you a different person when you came out the other end of that series?

McGoohan: Tired, that's all.

Troyer: Beyond that?

McGoohan: No, no....

Troyer: It wasn't purely psychoanalysis?

McGoohan: No, no, I never let any part that I play sort of take over. I think that that's nonsense when that happens. I think you should be able to go in and do it, learn your lines and do it. Some are more fatiguing that others, some are more emotionally exhausting than others. I mean, you can't play Hamlet without being drained or King Lear without being drained but to say that you lived through the day playing Lear or playing Hamlet before you go out the next night and go on to the stage, I think that's ludicrous.

Troyer: What about the notions that some actors, some people in other creative endeavors have, that we all have a finite bank of energy that each time one brings some of it up there's a little less left for next time, or for the other end of the road.

McGoohan: I think that the contrary is true. When one looks at people such as Arthur Rubenstein, people with tremendous talents and they are young men. They're young men at 75, they're young, 80 they're young! Their vitality, in fact, increases. Their energy increases. It just happens, I mean the force. The adrenalin increases. It just happens that the machinery of the body, the parts, the spare parts are wearing out a little bit...I think it increases and I know a lot of old folks who are young, young people.

Troyer: So the creative urge is a muscle, the more we flex it, the stronger it gets.

McGoohan: I think so, yeah. Yeah. It's just this stuff wears out. That's all.

Fifth Boy: Mr. McGoohan, when you began "The Prisoner," you began it in a decade in which a lot of people were used to secret agents. You very neatly saw the next decade coming. I thing you saw Watergate; the enemy within as opposed to the enemy without. I don't know if you can answer this, but if you were going to do the series again and you had to look aged to the 80's and you were thinking in terms of what you see as being the real enemy, not the storybook enemy but the enemy that's really going to hassle us. If you were going to look into the 80's now, what would you look to?

McGoohan: I think progress is the biggest enemy on earth, apart from oneself, and that goes with oneself, a two-handed pair with oneself and progress. I think we're gonna take good care of this planet shortly. They're making bigger and better bombs, faster planes, and all this stuff one day, I hate to say it, there's never been a weapon created yet on the face of the Earth that hadn't been used and that thing is gonna be used unless...I don't know how we're gonna stop it, not it's too late, I think.

Fifth Boy: Do you think maybe there's going to be a strong popular reaction against "Progress" in the future?

McGoohan: No, because we're run by the Pentagon, we're run by Madison Avenue, we're run by television, and as long as we accept those things and don't revolt we'll have to go along with the stream to the eventual avalanche.

Sixth Boy: We tend to view the threat, the Village there, as sort of a thing as something external like Madison Avenue, the media. How responsible are we for accepting this? Where do we become involved in being "unfree"?

McGoohan: Buying the product, to excess. As long as we go out and buy stuff, we're at their mercy. We're at the mercy of the advertiser and of course there are certain things that we need, but a lot of the stuff that is bought is not needed.

Sixth Boy: Did you regard the Village as an external thing or as something that we carry around with us all the time?

McGoohan: It was meant to be both. The external was the symbol, but it's within us all I think, don't you? This surrealist aspect; we all live in a little Village.

Troyer: Do we?

McGoohan: Your village may be different from other people's villages but we are all prisoners.

Troyer: Well, I know who the idiot is in mine.

McGoohan: Yes, Number One - same as me.

Seventh Boy: Is No. 1 the evil side of man's nature?

McGoohan: The greatest enemy that we have...No. 1 was depicted as an evil, governing force in this Village. So, who is this No. 1? We just see the No. 2's, the sidekicks. Now this overriding, evil force is at its most powerful within ourselves and we have constantly to fight it, I think, and that is why I made No. 1 an image of No. 6. His other half, his alter ego.

Troyer: Did you know when you first outlined the series in your own mind, the concept that No. 1 was going to turn out to be you, to be No. 6?

McGoohan: No, I didn't. That's an interesting question.

Troyer: When did you find out?

McGoohan: When it got very close to the last episode and I hadn't written it yet. And I had to sit down this terrible day and write the last episode and I knew it wasn't going to be something out of James Bond, and in the back of my mind there was some parallel with the character Six and the No. 1 and the rest. And then, I didn't even know exactly 'til I was about the third through the script, the last script.

Troyer: How about you colleagues, the other writers. Were they surprised?

McGoohan: Yep.

Troyer: Were they annoyed?

McGoohan: No.

Troyer: Did they decide it was untidy?

McGoohan: No, they used to come along from time to time and say, "Who's No. 1?" you see. And I told them , "It's a secret" until I actually sat down and wrote it - and it was, actually; they didn't know until I handed out the script.

Troyer: But were they disappointed by that...?

McGoohan: No, they liked it. They said they always knew it was going to be him.

Troyer: (laughs) Once you told them.

McGoohan: Few of them did really. Nobody really knew. No.

Troyer: Why the double mask? Why the monkey face?

McGoohan: Oh, dear. Yeah, well, we're all supposed to come from these things, you know. It's the same with the penny farthing symbol bicycle thing. Progress. I don't think we've progressed much. But the monkey thing was, according to various theories extant today, that we all come from the original ape, so I just used that as a symbol, you know. The bestial thing and then the other bestial face behind it which was laughing, jeering and jabbering like a monkey.

Eighth Boy: Mr. McGoohan, during the last episode, Fall Out, we see the Prisoner. He's smiling and laughing and dancing for the first time and yet later on the very last scene is exactly the some as the very first scene where he's driving off with his familiar stern face. My question is, has the Prisoner between the first and the last episode actually changed any?

McGoohan: Ah, no, I think he's essentially the same. I think he got slightly exhilarated by the fact that he got out of this mythical place and felt like doing a little skip and a dance, and singing a bit, and felt very happy to be going home with his little buddy, the Butler, you know. And we never did a cut of him when that door opened. We just saw the door open and he went in. So, you never knew whether his exhilaration was lost when he saw that sinister door that was left like an unfinished symphony.

Ninth Boy: In the final episode, does the Prisoner really consider becoming the leader of the Village?

McGoohan: No. He does not. He just wants to get out and he uses a technique which he hadn't used before that, which was violence, which is sad, but he does; and that's how he gets out and then, of course, in the final episode, he goes back to his little apartment place and he has his little valet guy with him and the door opens on its own when he goes in the car. There you know it's gonna start over again because we continue to be Prisoners.

Ninth Boy: And that leads to my last question, what would the Prisoner be likely to do with his newfound freedom?

McGoohan: He hasn't got it. Which is the whole point. When that door opens on its own and there's no one behind it, exactly the same as all the doors in the Village open, you know that somebody's waiting in there to start it all over again. He's got no freedom. Freedom is a myth. There's no final conclusion to it. Ah, and I was very fortunate to be able to do something as audacious as that with no final conclusion to it because people do want the word "THE END" put up there. Now the final two words for that thing should have been "THE BEGINNING".

Troyer: This is kind of a banal question, I guess, but if you could leave one sentence or paragraph in the head of everyone who watched the Prisoner series, the whole series, one thing for them to carry around for awhile, when it was over, what would it be?

McGoohan: Be seeing you.

Troyer: Just that?...enigmatic to the end.

McGoohan: Be seeing you. That means quite a lot.

Troyer: It does indeed.

McGoohan: Be seeing you. Yeah.

|

|