|

The Multiversity

Wednesday, March 18, 2015 | Comics

The Multiversity is a limited series of interrelated one-shots set in the DC Multiverse in The New 52, a collection of universes seen in publications by DC Comics. The one-shots in the series are written by Grant Morrison, each with a different artist. The Multiversity began in August 2014.

The Multiversity is a limited series of interrelated one-shots set in the DC Multiverse in The New 52, a collection of universes seen in publications by DC Comics. The one-shots in the series are written by Grant Morrison, each with a different artist. The Multiversity began in August 2014.

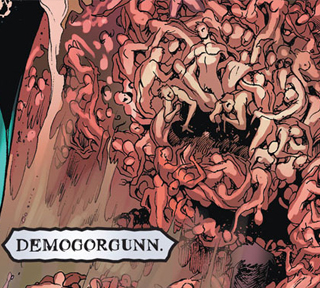

The Multiversity features a new story about the multiverse being invaded by a race of demonic destroyers known as the Gentry. The Gentry is a group of powerful beings seeking to make the Multiverse mirror their horror. They hail from a place outside of the Multiverse, said to be the "opposite of everything natural". Various heroes from across different universes are forced to band together to face this inter-dimensional threat, initiating the "Battle for All Creation". Morrison noted in an interview that each member is "a villain archetype taken to the limit. Intellectron is the mastermind taken to the limit. Dame Merciless is the femme fatale taken to the demonic limit. Demogorgunn is the zombie horde taken to the limit, and so on through the rest of them. Lord Broken is the madhouse, Arkham Asylum taken it to the limit."

The series contains 9 one-shot issues, with two of them being bookends. The bookends will function as a two-part story, which Morrison describes as an "80-page giant DC super-spectacular story". With each one-shot taking place in a different universe, each publication will also feature different trade dress and a different storytelling approach, Morrison explains, "each comic looks like it comes from a different parallel world, so they're all slightly different."

Morrison stated that when developing the series, he had to think of a way for the featured universes to communicate with each other. He recalled "The Flash of Two Worlds" story line from The Flash #123, where the adventures of the Golden Age Flash, Jay Garrick of Earth-2, were documented as a comic book on Earth-1. He incorporated this device into The Multiversity, stating "they're reading each other's adventures, so there's some way that if a real big emergency arises, they can communicate using comic books. So each world has a comic from the previous world which has clues to the disaster that's coming their way, and they all have to basically start communicating using writers and artists so it's my big, big statement." Morrison further explained how the device is used to create a cohesive story, "it's almost like a baton race or a relay race where each of the worlds can read a comic book that's published in their world but which tells the adventures of the previous world. The characters are actually reading the series along with the readers."

- Text from Wikipedia except where denoted, with bits thrown in from DC, and, of course, Morrison interviews.

- David Uzumeri has done a wonderful job annotating most of the issues at Comics Alliance

- The Multiversity: House of Heroes

- The Society of Super-Heroes: Conquerors from the Counter-World

- The Just: #earthme

- Pax Americana: In Which We Burn

- Thunderworld Adventures: Captain Marvel and the Day That Never Was!

- Guidebook: Maps and Legends

- Mastermen: Splendour Falls

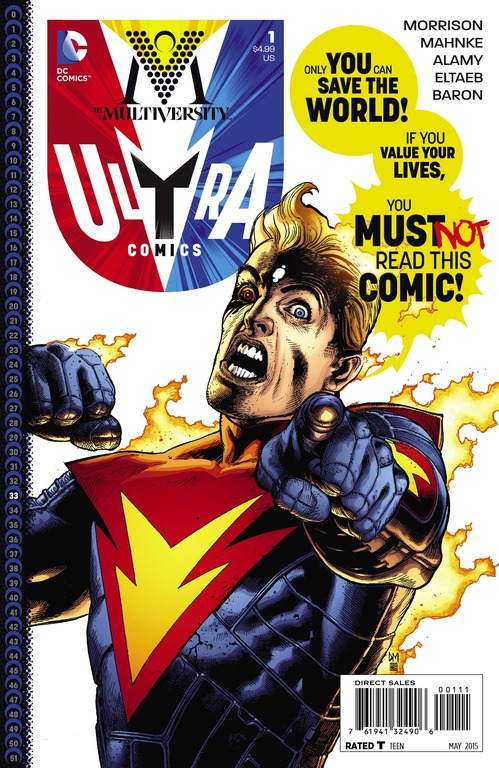

- Ultra Comics

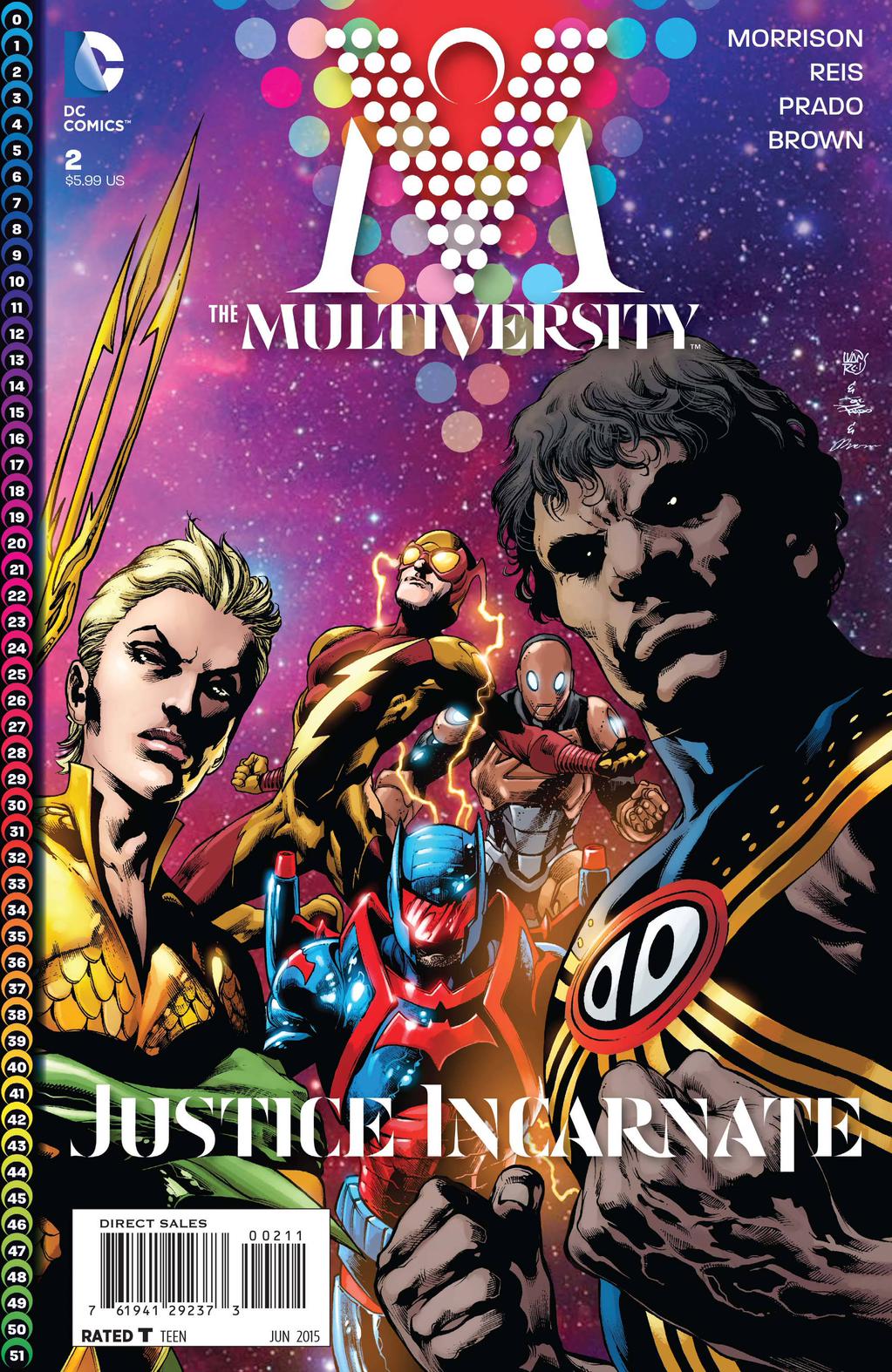

- The Multiversity #2

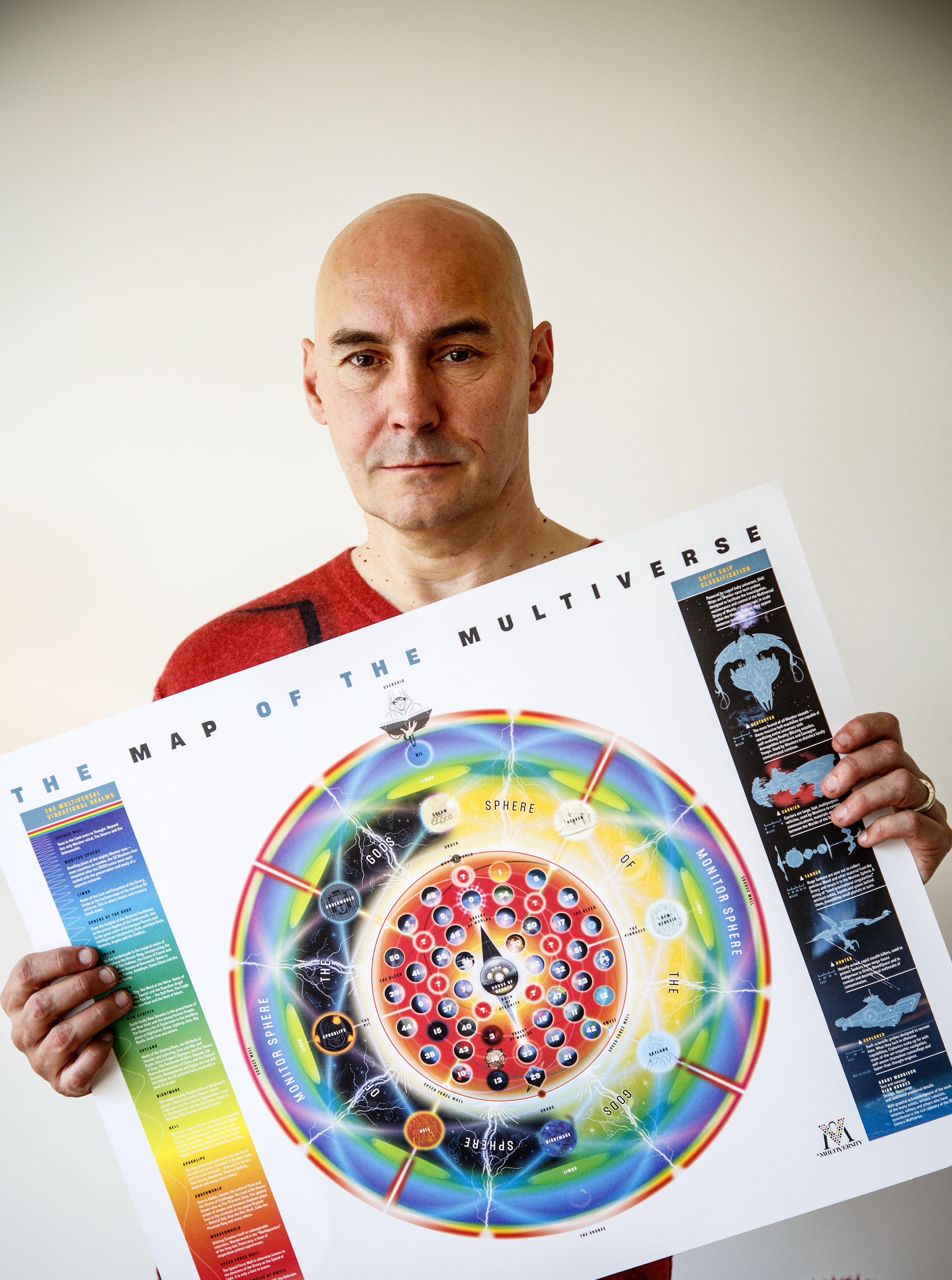

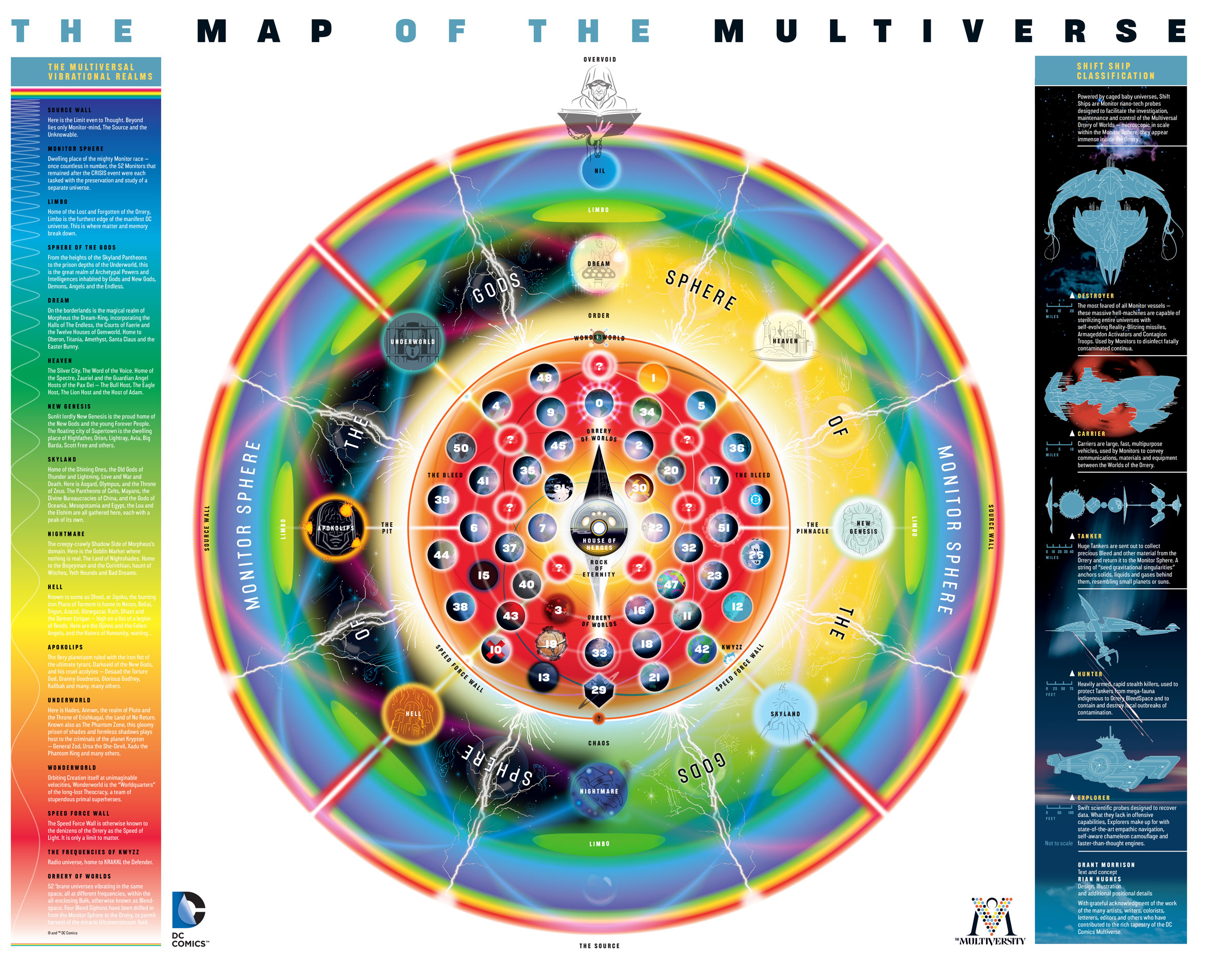

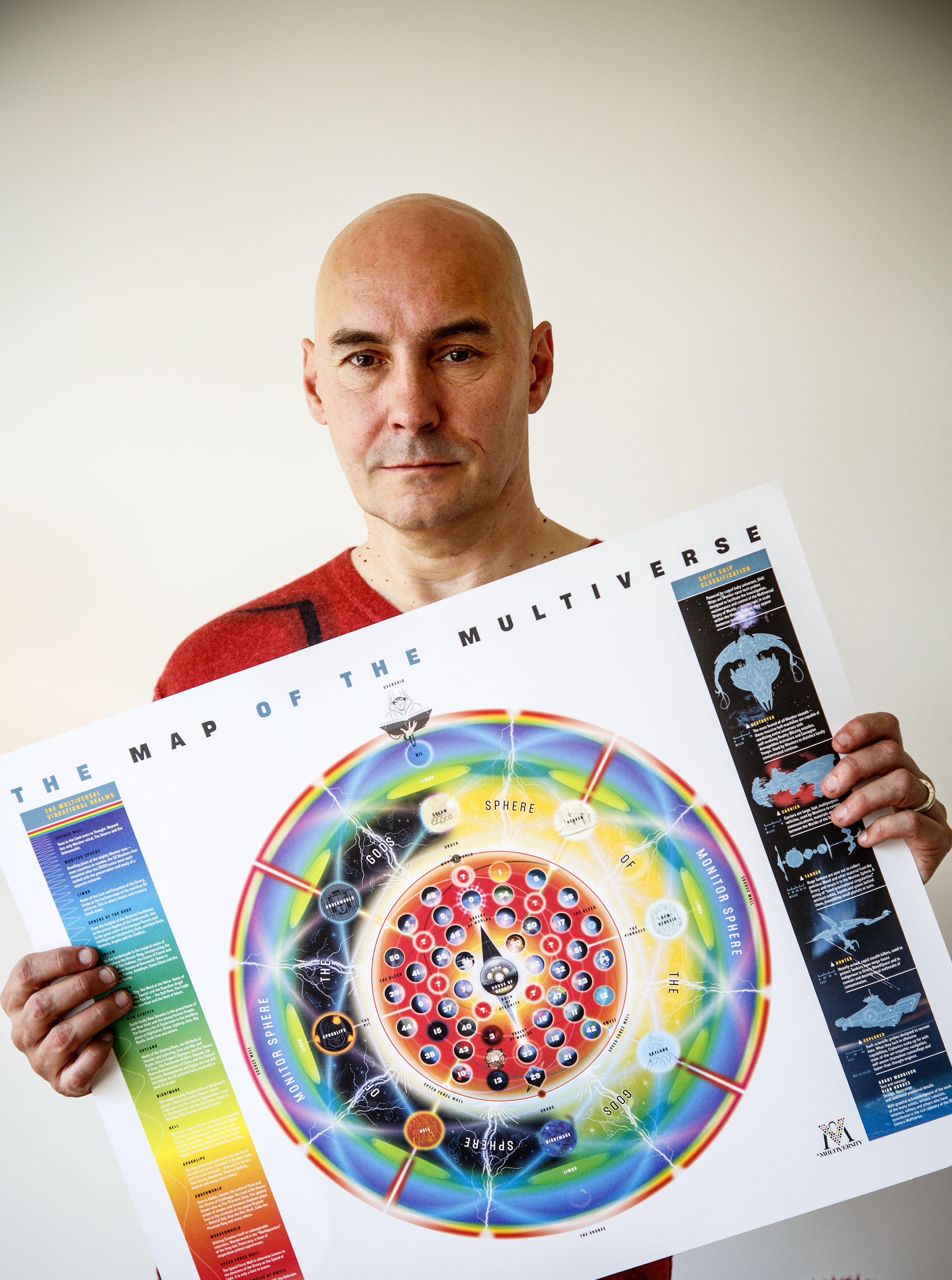

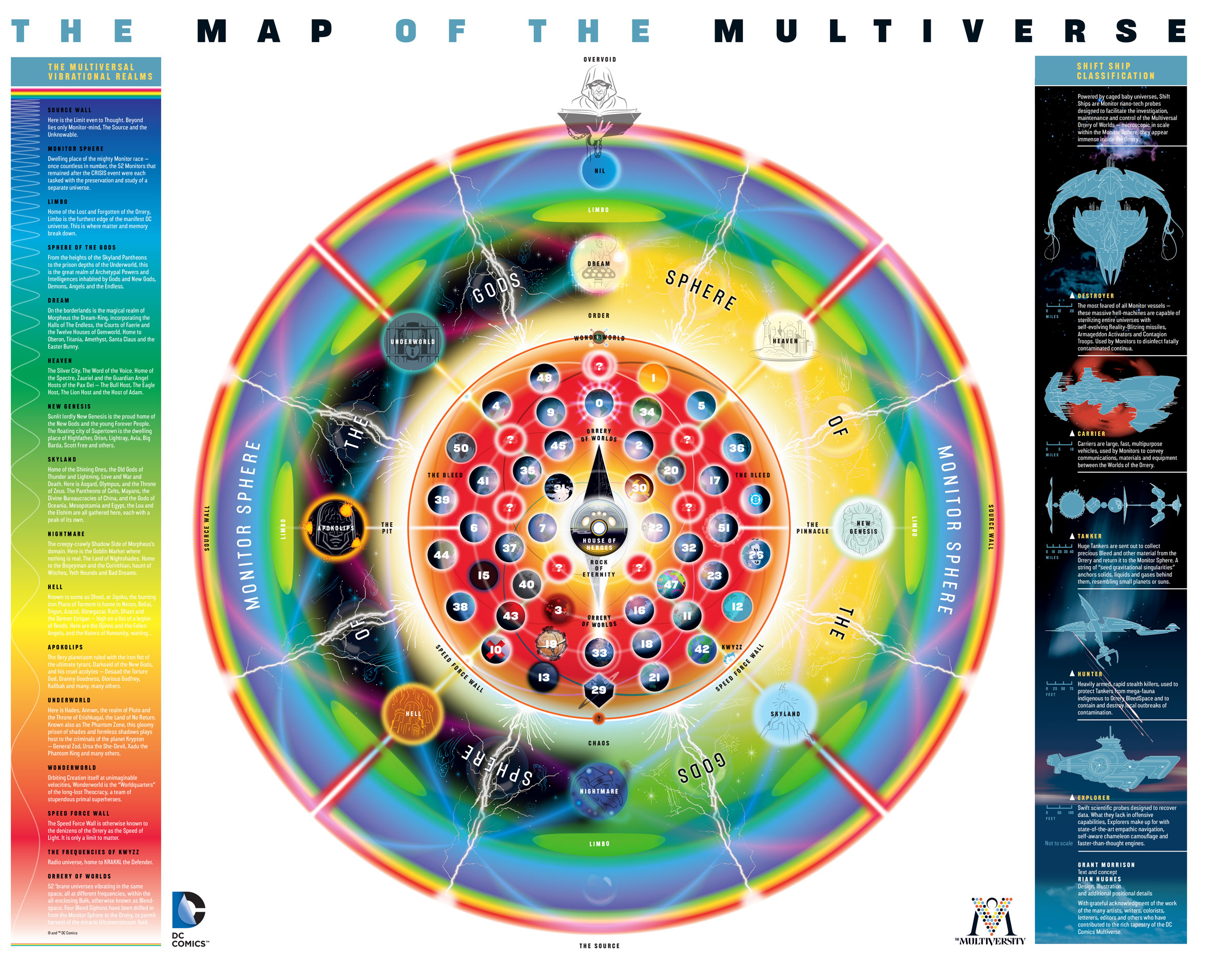

Map of the Multiverse

View the Morrison Original Sketch

Morrison and artist Rian Hughes mapped the entire Multiverse out.

View the Morrison Original Sketch

Morrison and artist Rian Hughes mapped the entire Multiverse out.

You need Flash to navigate this site.

The Gentry

A menace from beyond the multiverse, the Gentry menace all the worlds with their corruption.

The Gentry kind of represent all those things that we just accept. To me, the result I'm actually seeing is a kind of soul weariness, a cynicism, a sickness that permeates culture. I think we're all fed up with ourselves and we're just waiting to be destroyed by the other.

Capable of twists the laws of the physics and corrupt their victims, The Gentry are living ideas with no regards towards life. They attacked and destroyed earth-7, leaving only Thunderer as survival. Only the intervention of Nix Uotan saved Thunderer; instead he was captured an corrupted by the Gentry and used as their agent to attack earths 8 ,20 and 51, releasing Darkseid in the multiverse. With earth after earth being attacked, the Gentry grows stronger. And on each world, the Gentry attacked in different ways and usually through agents. Until now, however, is unknow if the Gentry is operating alone or if they are the underlings of an even darker power. It has bee speculated than each one represents supervillians archetypes powered up to godlike levels and twisted to lovecraft-like entities shapes.

They're demon ideas and we incubate them and they form. We can feel them, but we don't quite know how to display them and what they're doing. It's been portrayed that our imaginative space has become degraded. Where once we had Star Trek now we have The Walking Dead. We see our civilization as something that's basically, ultimately doomed. And maybe a generation ago we saw our civilization as something that would naturally be carried into the stars, and have this fantastic utopian future. So Multiverse is all about that, and Ultra is specifically about the idea that we have impoverished a neighborhood, and once you've impoverished a neighborhood then you come in to gentrify it. You've made it very comfortable for the monsters to cultivate.

|

IntellectronMastermind (the super evil genius archtype) taken to the limit.

Earth-4 was posible under the attack of Intellectron, same as earth-33. |

|

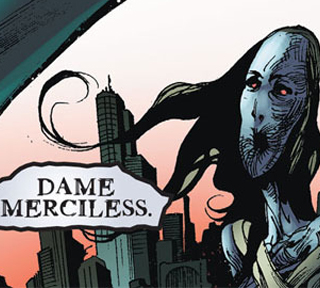

Dame MercilessFemme Fatale taken to the demonic limit.

On earth-16, Dame Merciless infected the dreams of the world and the mind of Megamorpho, Alexis Luthor and many others. |

|

DemogorgunnThe Zombie Horde taken to the limit.

On earth-5, Demogorgunn, manifested as the plurality of the legion of Sivanas attacked the heart of the magic, the rock of eternity. |

|

Lord BrokenThe Madhouse, Arkham Asylum taken it to the limit.

Lord Broken infected the dreams of Overman in earth-10. |

|

HellmachineThe Mindless Brute Beast taken to the limit.

Hellmachine attacked directely the House of Heroes. |

Empty Hand

Powerful and malevolent force behind the Gentry, Nix Uotan's corruption, the release of Darkseid from his tomb, and the massacre and subsequent revival of Earth-42's heroes. True identity and goals unknown

Powerful and malevolent force behind the Gentry, Nix Uotan's corruption, the release of Darkseid from his tomb, and the massacre and subsequent revival of Earth-42's heroes. True identity and goals unknown

Empty is thy hand.

The Empty Hand is symbolic in the DC Universe as having to do with creation, popping up when Krona originally saw the origin of the Universe, the battle between Spectre and Anti-Monitor in Crisis on Infinite Earths, Alexander Luthor in Infinite Crisis, and now Multiversity where it appears to be the main villain behind the Gentry's attack.

Master of the Gentry, the Empty Hand masterminded the utter destruction of the laws of physics and the residents of Earth-7 where he now resides and created robotic servants in the Lil' Leaguers of Earth-42 to spy on the heroes of the DC Multiverse. When confronted by heroes of the newly formed Justice Incarnate, the Empty Hand explained that The Gentry's incursion into the Multiverse was simply to conduct an initial assessment of the heroes strength and to construct the Oblivion Machine that will ultimately bring an end to the never ending story. He also states that his legions feed on the carcass of a previous victim he calls Multiverse-2 and then sends the heroes away.

There's a very bad idea hidden inside the comic book (Ultra Comics #1), and the bad idea will be revealed if you continue to read it, so you may not want to know this. The bad idea is ultimately not that you stop reading the story, but the story dies, which by implication means that you one day will also die. The new horror that's revealed is the Oblivion Machine in Ultra Comics; consuming comics is devouring the hours and the minutes of your lives, and you're actually being vampirized by your entertainment media. That's the ghost in Ultra Comics, that you're being devoured by the story that you're consuming, because you could be out there meeting the girl of your dreams or flying out a microlight. It's about the things that we consume, the pictures that we love to watch.

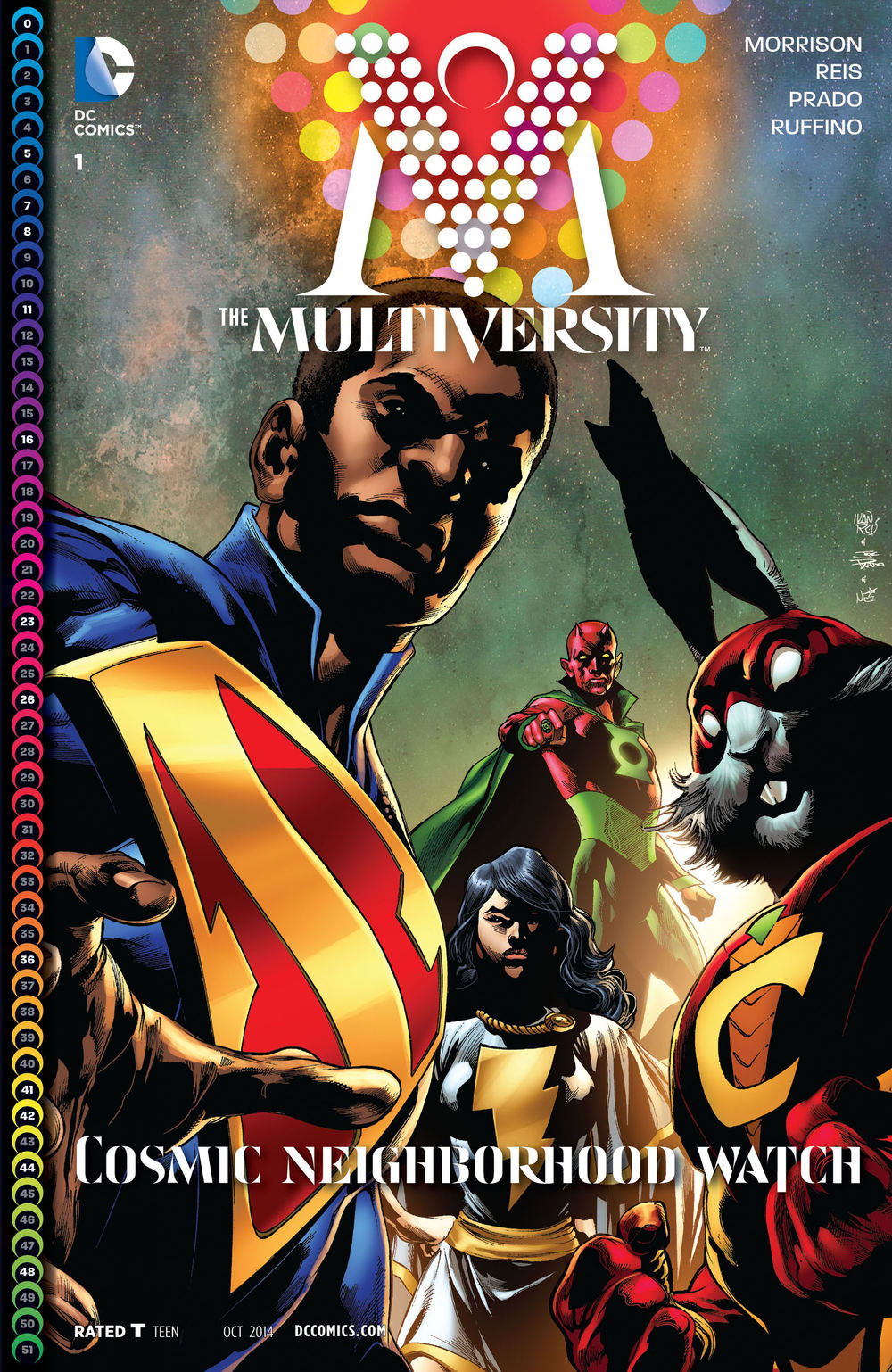

The Multiversity #1:

House of Heroes

View the Morrison Cover Variant

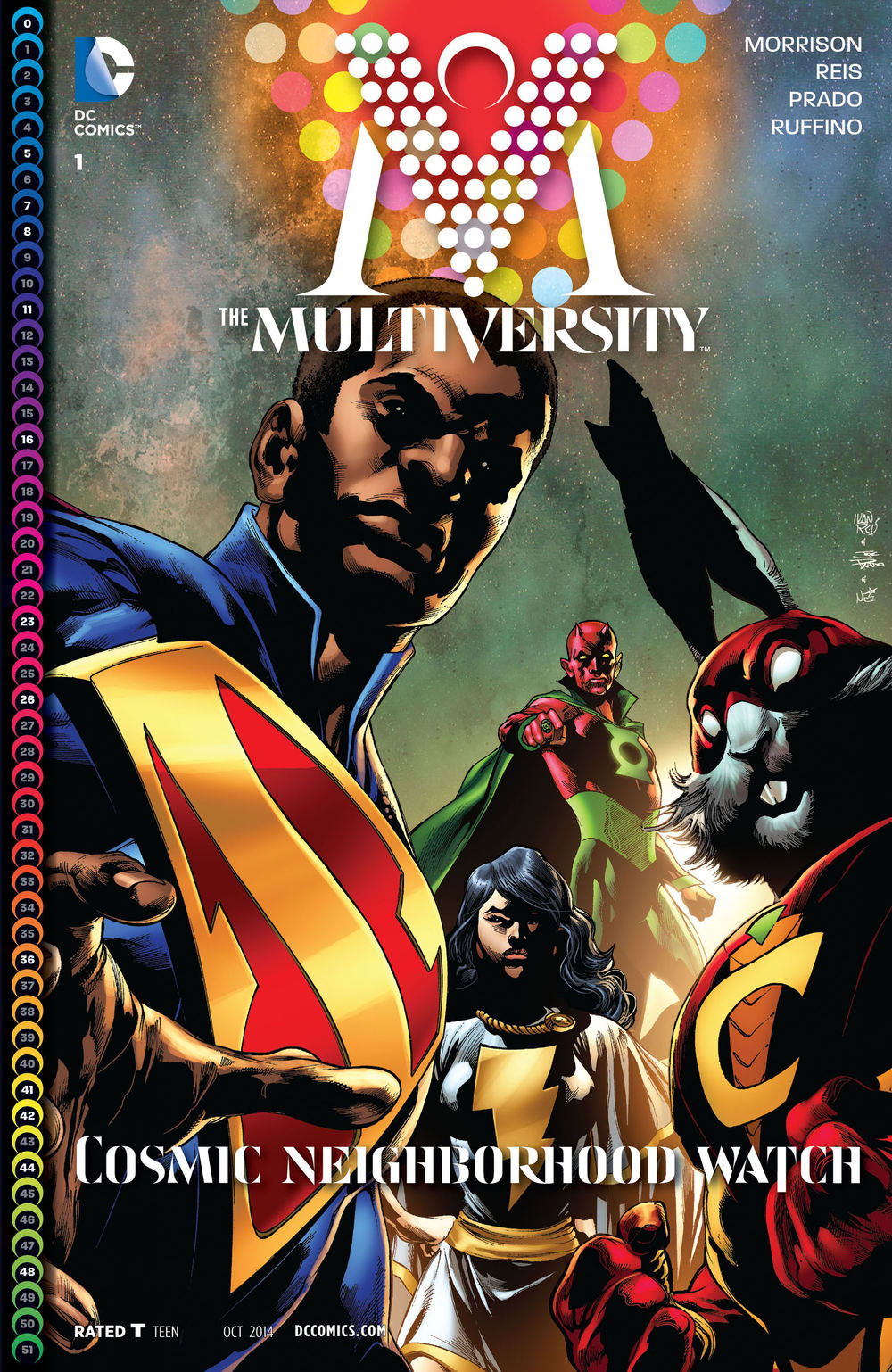

The first chapter, illustrated by Ivan Reis, Joe Prado, and Nei Ruffino, The Multiversity features Calvin Ellis, President of the United States and Superman of Earth-23. Morrison describes The Multiversity as a big team book, featuring characters from all over the Multiverse, the team looks "after the welfare of the entire multiverse and they're headquartered in a place called the Multiversity" Morrison compares the team to a Justice League of the Multiverse. The team will include characters such as Captain Carrot, and Thunderer, an Aboriginal version of Marvel Comics' Thor. It was published in August 2014.

View the Morrison Cover Variant

The first chapter, illustrated by Ivan Reis, Joe Prado, and Nei Ruffino, The Multiversity features Calvin Ellis, President of the United States and Superman of Earth-23. Morrison describes The Multiversity as a big team book, featuring characters from all over the Multiverse, the team looks "after the welfare of the entire multiverse and they're headquartered in a place called the Multiversity" Morrison compares the team to a Justice League of the Multiverse. The team will include characters such as Captain Carrot, and Thunderer, an Aboriginal version of Marvel Comics' Thor. It was published in August 2014.

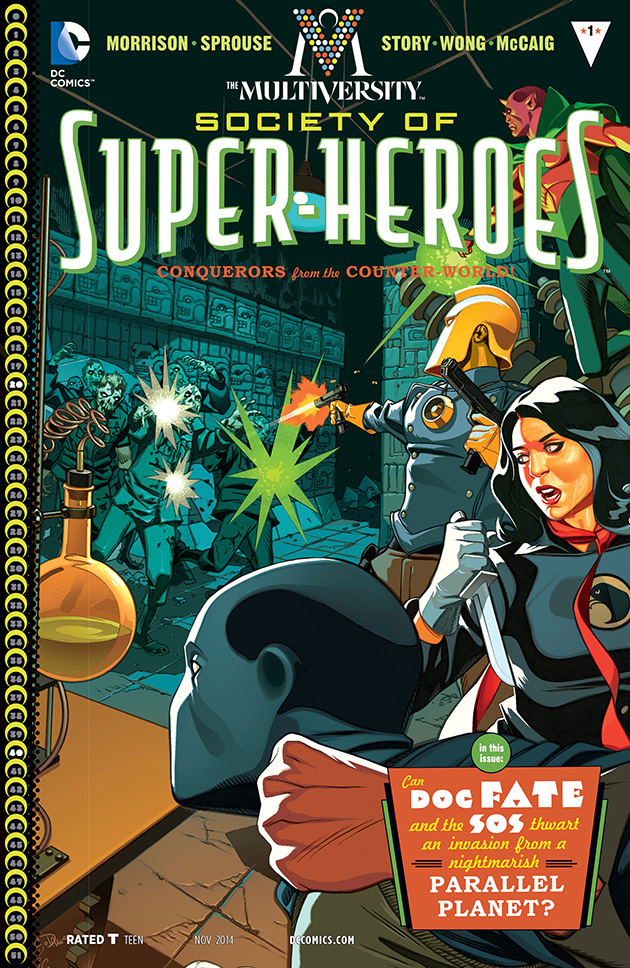

The Society of Super-Heroes:

Conquerors from the Counter-World

View the Morrison Cover Variant

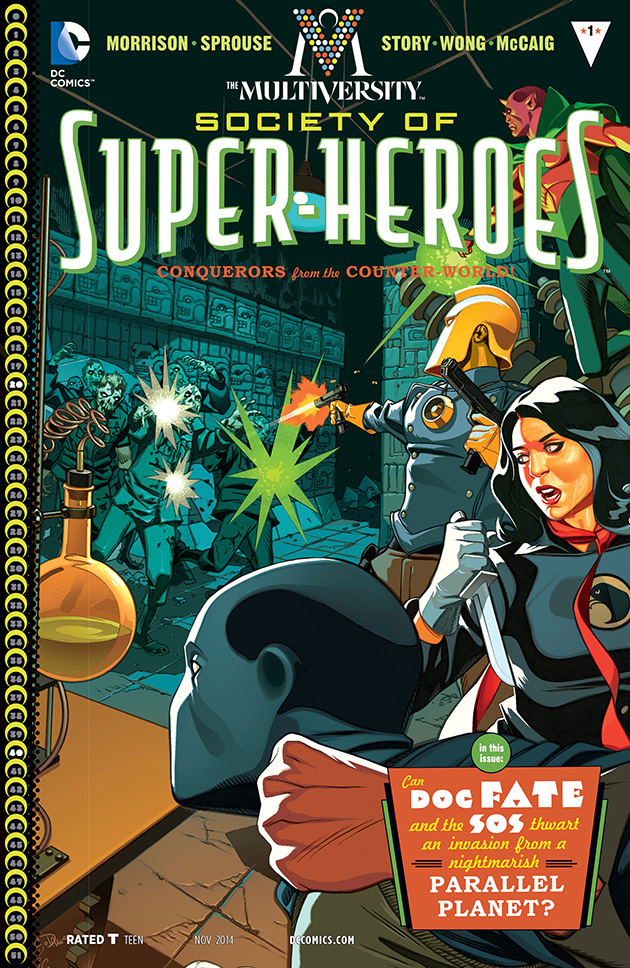

The second chapter, illustrated by Chris Sprouse and Karl Story, The Society of Super-Heroes: Conquerors of the Counter-World ("SOS") featured the Society of Super-Heroes from Earth-20 and their villainous counterparts from Earth-40. The Society of Superheroes is a pulp-style Justice Society of America, led by Doc Fate, who had previously appeared in Superman Beyond, Morrison describes him as "kind of a Doc Savage-come-Doctor Fate guy who teams with the Mighty Atom, the Immortal Man, Lady Blackhawk and her Blackhawks and Abin Sur, the Green Lantern. It's all kind of a 1940s retro thing. As I say, it's a pulp take on superheroes," along with other recreated "primitive pulp characters". Morrison described this Earth as only having a population of "two billion people, even though it's 2012." There has been a recent global war akin to World War II, albeit directed against a scion of the al-Ghul dynasty and an alliance of Arab/Islamic states, the "Desert Crescent"." Earth-40 invaders devastate Earth-20 as its supervillains wage global war against the Society of Super Heroes in defence of their home alternate. It was published in September 2014.

View the Morrison Cover Variant

The second chapter, illustrated by Chris Sprouse and Karl Story, The Society of Super-Heroes: Conquerors of the Counter-World ("SOS") featured the Society of Super-Heroes from Earth-20 and their villainous counterparts from Earth-40. The Society of Superheroes is a pulp-style Justice Society of America, led by Doc Fate, who had previously appeared in Superman Beyond, Morrison describes him as "kind of a Doc Savage-come-Doctor Fate guy who teams with the Mighty Atom, the Immortal Man, Lady Blackhawk and her Blackhawks and Abin Sur, the Green Lantern. It's all kind of a 1940s retro thing. As I say, it's a pulp take on superheroes," along with other recreated "primitive pulp characters". Morrison described this Earth as only having a population of "two billion people, even though it's 2012." There has been a recent global war akin to World War II, albeit directed against a scion of the al-Ghul dynasty and an alliance of Arab/Islamic states, the "Desert Crescent"." Earth-40 invaders devastate Earth-20 as its supervillains wage global war against the Society of Super Heroes in defence of their home alternate. It was published in September 2014.

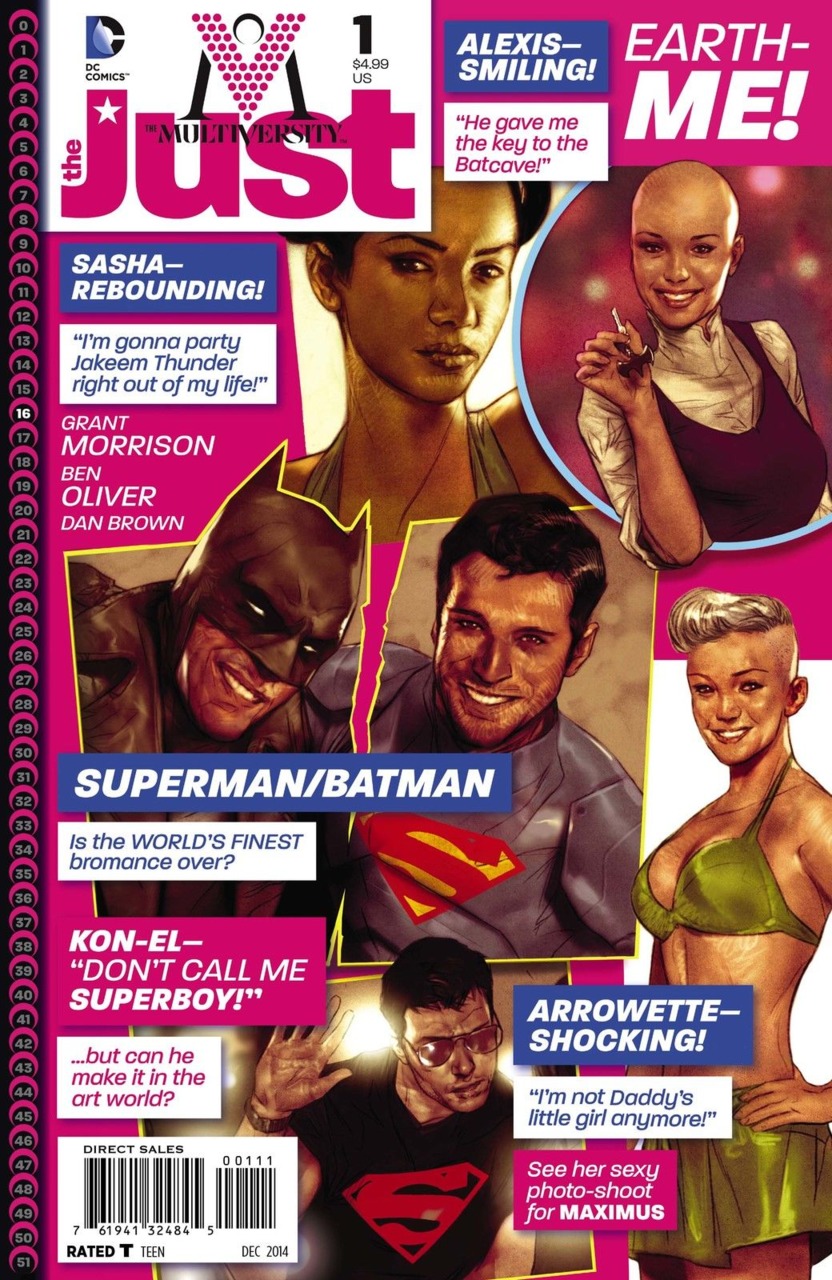

The Just:

#earthme

View the Morrison Cover Variant

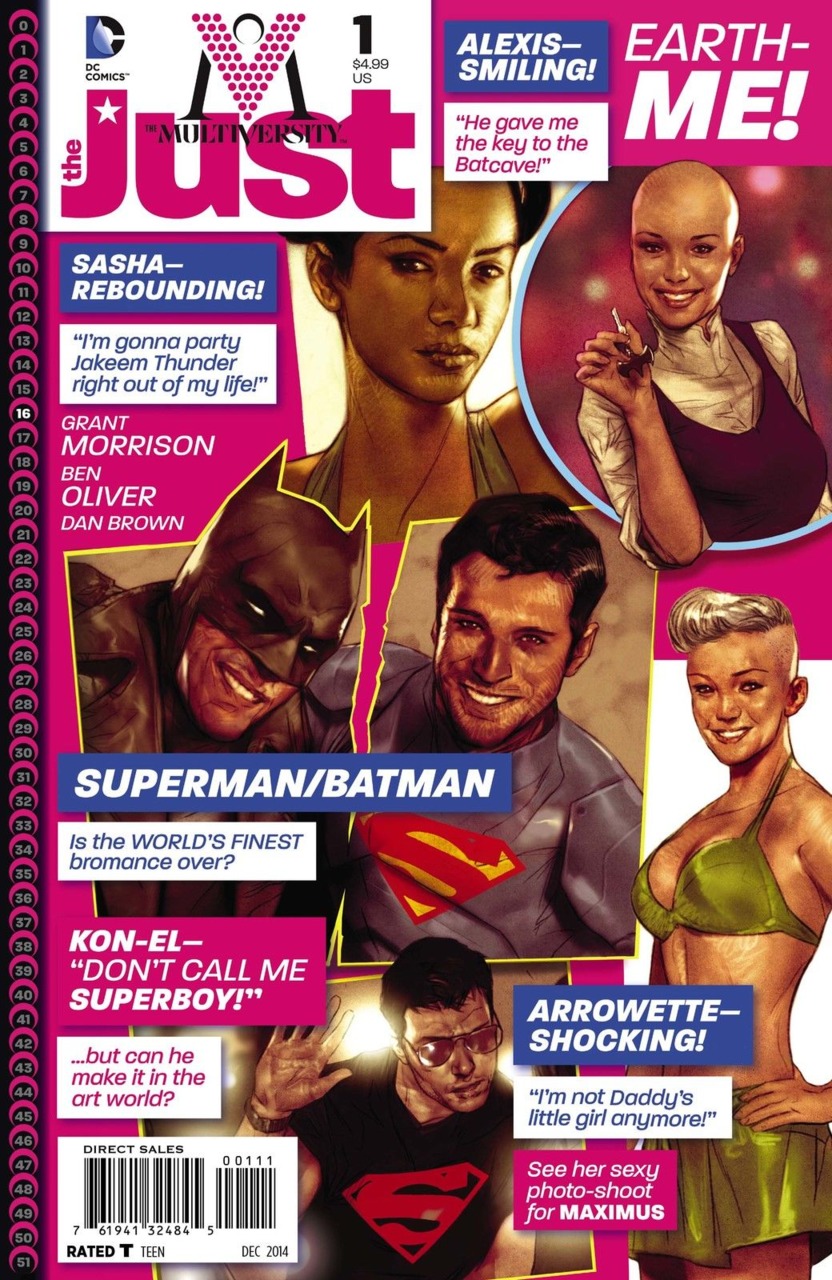

The third chapter, illustrated by Ben Oliver, The Just features a world of legacy characters and children of superheroes from Earth-16,[36] such as Connor Hawke and the Super-Sons, "this is those guys but they're not the main heroes. There's a whole younger generation of heroes – kind of media brats almost." Morrison describes them as "children of superheroes – a son of Superman, a son of Batman, etc. – who exist in a world where they have incredible abilities, but the previous generation had ushered in a utopia, so they don't really have any notion of where to direct it, and they're very unhappy with the world as is." Morrison cites MTV's The Hills as his inspiration for The Just. Morrison described the idea as "What happens when your mom and dad fix everything? Superman, Batman and Wonder Woman have kind of fixed everything so the kids have nothing to do," instead resorting to battle reenactments, "these kids, they dress up but they've never fought anything." Morrison had originally conceptualized a "Super-Sons" story as part of his All-Star Superman series, where Superman and Batman had stopped all crime, noting "One day, I might get to them or some version of it. There's a little bit of that in the "Multiversity" series that I'm doing". Morrison originally designated this universe as Earth-11. The one-shot was published in October 2014.

View the Morrison Cover Variant

The third chapter, illustrated by Ben Oliver, The Just features a world of legacy characters and children of superheroes from Earth-16,[36] such as Connor Hawke and the Super-Sons, "this is those guys but they're not the main heroes. There's a whole younger generation of heroes – kind of media brats almost." Morrison describes them as "children of superheroes – a son of Superman, a son of Batman, etc. – who exist in a world where they have incredible abilities, but the previous generation had ushered in a utopia, so they don't really have any notion of where to direct it, and they're very unhappy with the world as is." Morrison cites MTV's The Hills as his inspiration for The Just. Morrison described the idea as "What happens when your mom and dad fix everything? Superman, Batman and Wonder Woman have kind of fixed everything so the kids have nothing to do," instead resorting to battle reenactments, "these kids, they dress up but they've never fought anything." Morrison had originally conceptualized a "Super-Sons" story as part of his All-Star Superman series, where Superman and Batman had stopped all crime, noting "One day, I might get to them or some version of it. There's a little bit of that in the "Multiversity" series that I'm doing". Morrison originally designated this universe as Earth-11. The one-shot was published in October 2014.

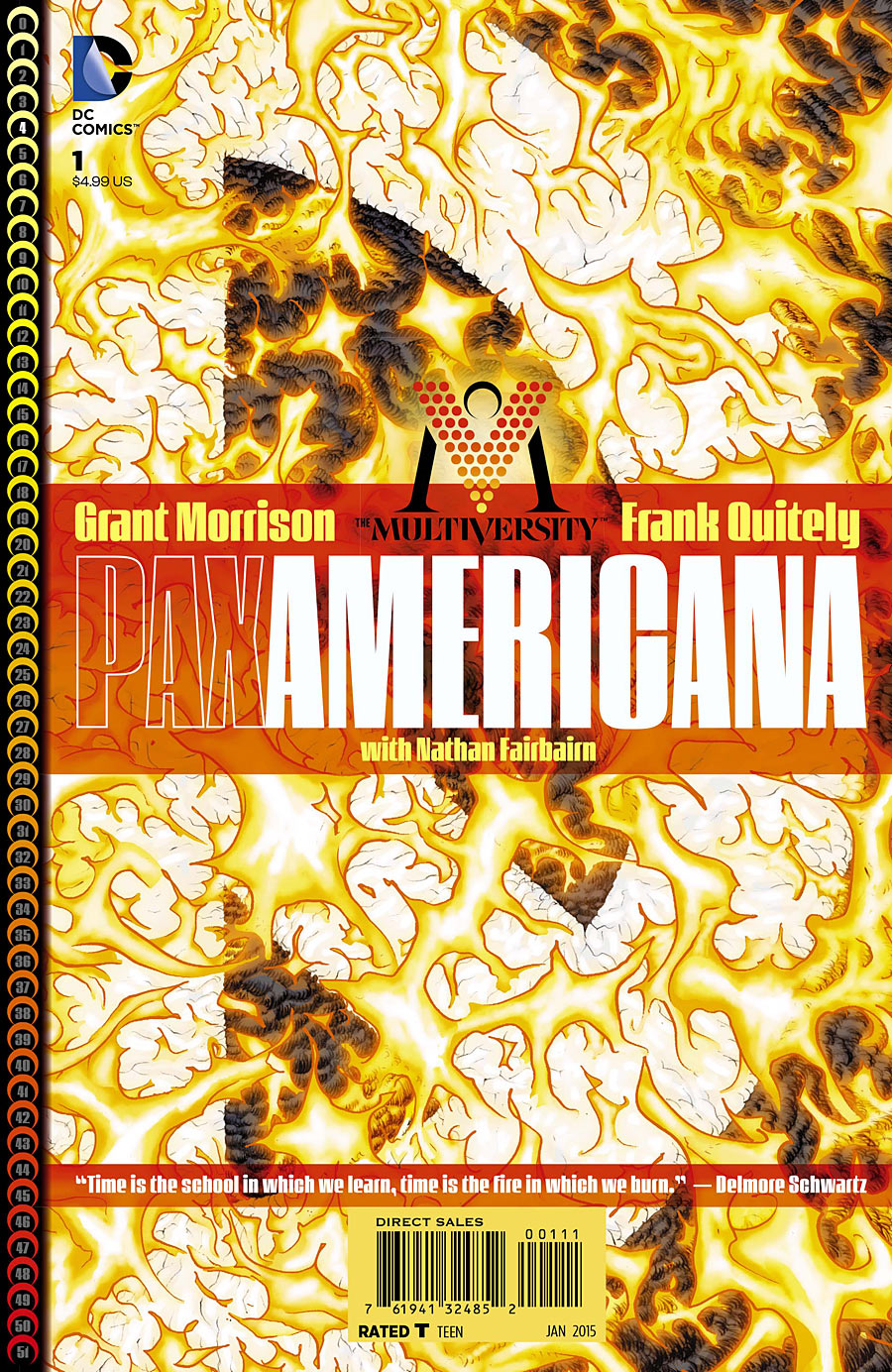

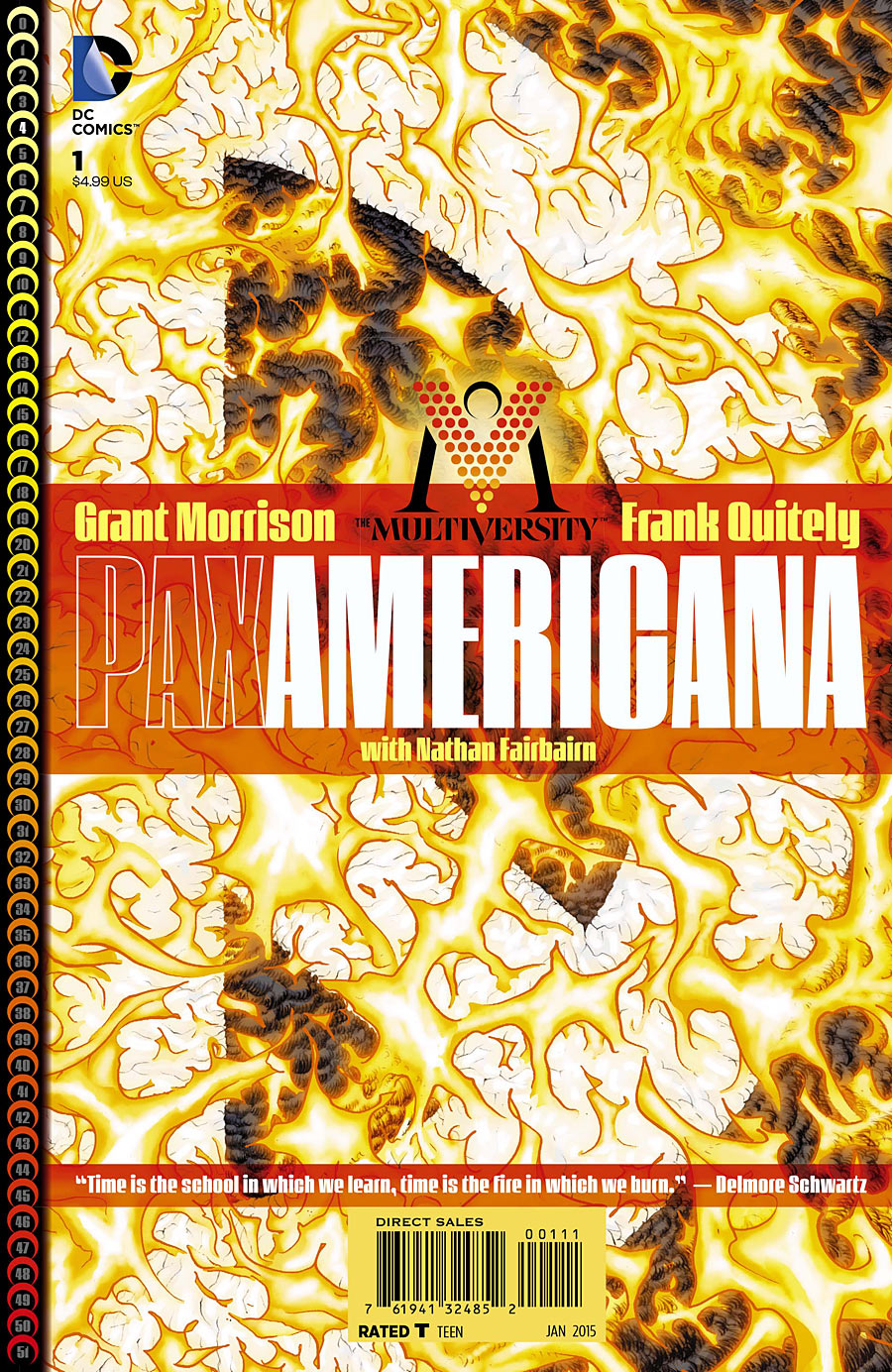

Pax Americana:

In Which We Burn

View the Morrison Cover Variant

The fourth chapter, illustrated by Frank Quitely, Pax Americana: In Which We Burn takes place on Earth-4 and features characters from Charlton Comics. It has been described by Morrison as "if Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons had pitched the Watchmen now, rooted in a contemporary political landscape." Rather than the Cold War focus of Watchmen, the title's focus will be international terrorism and conspiracy in a world of superheroes. The story will be told with an 8-panel grid, similar to Watchmen's 9-panel grid layout. The story is based around musical harmonics, as each world in the Multiverse vibrates at a different frequency, with Quitely explaining, "music, and vibration... musical vibrations, the octave, the eight as a repeated motive, and creating patterns leading the eye around the page in a specific way." Morrison describes Pax Americana as his Citizen Kane. The Captain Atom of this universe had been introduced in Final Crisis as his world's analogue to Superman. Morrison describes The Question as "a little bit like Rorschach but absolutely nothing like Rorschach." Peacemaker is described as a good guy, but assassinates the President of the United States. The story revolves around the assassination, and the failures on part of the Charlton characters. The one-shot was published in November 2014.

View the Morrison Cover Variant

The fourth chapter, illustrated by Frank Quitely, Pax Americana: In Which We Burn takes place on Earth-4 and features characters from Charlton Comics. It has been described by Morrison as "if Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons had pitched the Watchmen now, rooted in a contemporary political landscape." Rather than the Cold War focus of Watchmen, the title's focus will be international terrorism and conspiracy in a world of superheroes. The story will be told with an 8-panel grid, similar to Watchmen's 9-panel grid layout. The story is based around musical harmonics, as each world in the Multiverse vibrates at a different frequency, with Quitely explaining, "music, and vibration... musical vibrations, the octave, the eight as a repeated motive, and creating patterns leading the eye around the page in a specific way." Morrison describes Pax Americana as his Citizen Kane. The Captain Atom of this universe had been introduced in Final Crisis as his world's analogue to Superman. Morrison describes The Question as "a little bit like Rorschach but absolutely nothing like Rorschach." Peacemaker is described as a good guy, but assassinates the President of the United States. The story revolves around the assassination, and the failures on part of the Charlton characters. The one-shot was published in November 2014.

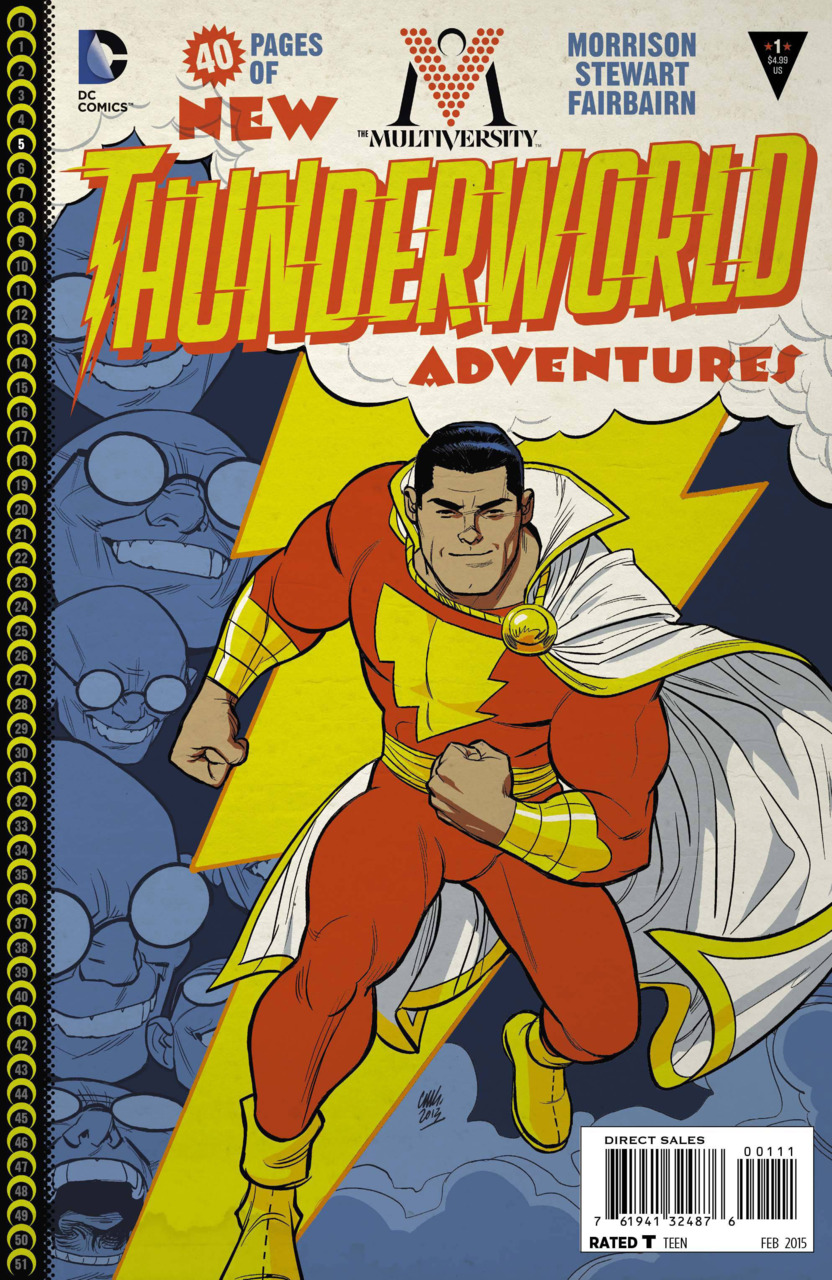

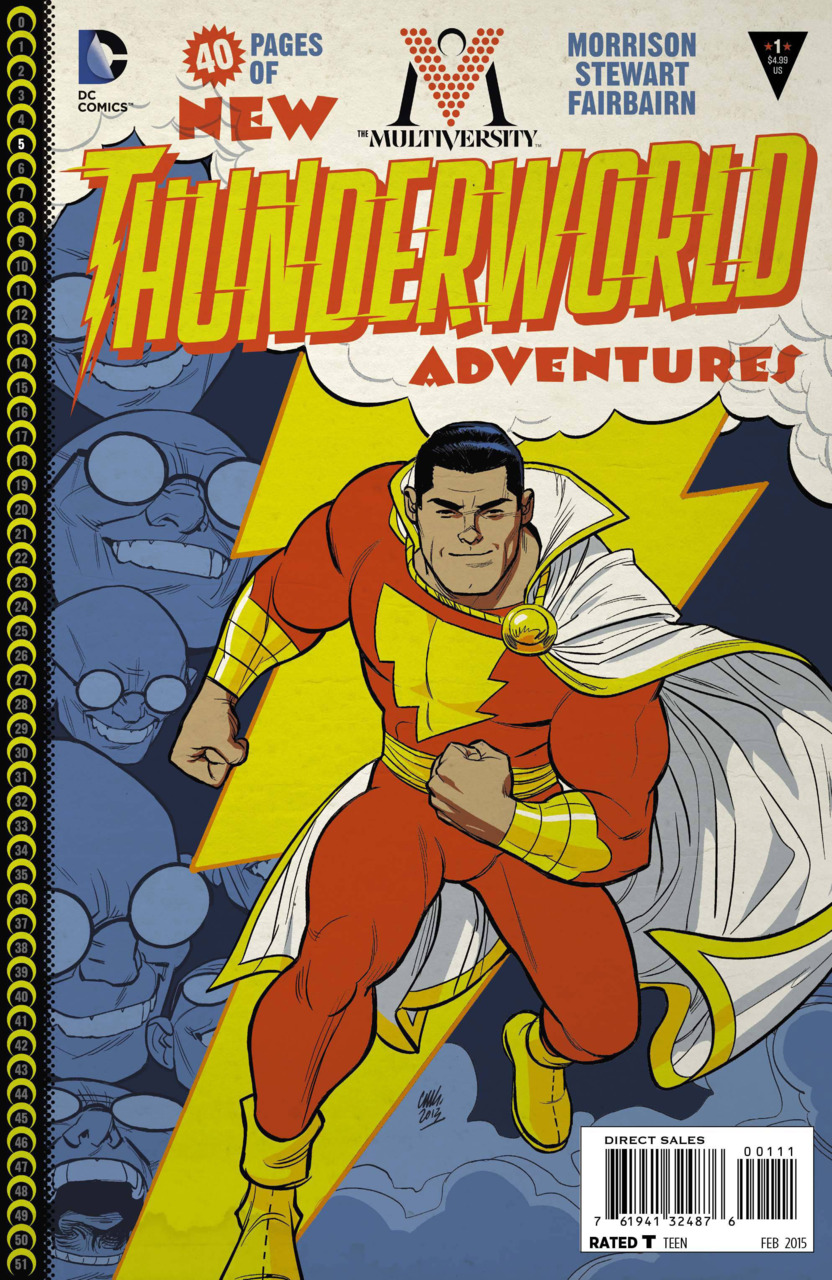

Thunderworld Adventures:

Captain Marvel and the Day That Never Was!

View the Morrison Cover Variant

The fifth chapter, illustrated by Cameron Stewart, Thunderworld Adventures takes place on Earth-5 and features characters from the Captain Marvel family. Morrison described this book as "a classic Shazam book but it's done in a way almost like a PIXAR movie or the way we did All Star Superman. It captures the spirit of those characters without being nostalgic or out of date." Morrison noted it as his "attempt to see if you can get the pure note of Captain Marvel, with no irony and no camp and just make it work for everyone. It's like a myth, a little folk tale. It's pure." The one-shot was published in December 2014. It dealt with Doctor Sivana attempting to hijack the Rock of Eternity, which endows the Marvel Family with their supernatural abilities and empower himself and his three children Magnificus, Georgia and Thaddeus Junior. It also enabled Sivana to add an extraneous calendar day to the usual week, but reliance on an alternate-universe "Legion of Sivanas" meant that his alternate versions shortchanged him, leading to only an eight-hour "Sivanaday" and his ultimate defeat at the hands of his nemesis.

View the Morrison Cover Variant

The fifth chapter, illustrated by Cameron Stewart, Thunderworld Adventures takes place on Earth-5 and features characters from the Captain Marvel family. Morrison described this book as "a classic Shazam book but it's done in a way almost like a PIXAR movie or the way we did All Star Superman. It captures the spirit of those characters without being nostalgic or out of date." Morrison noted it as his "attempt to see if you can get the pure note of Captain Marvel, with no irony and no camp and just make it work for everyone. It's like a myth, a little folk tale. It's pure." The one-shot was published in December 2014. It dealt with Doctor Sivana attempting to hijack the Rock of Eternity, which endows the Marvel Family with their supernatural abilities and empower himself and his three children Magnificus, Georgia and Thaddeus Junior. It also enabled Sivana to add an extraneous calendar day to the usual week, but reliance on an alternate-universe "Legion of Sivanas" meant that his alternate versions shortchanged him, leading to only an eight-hour "Sivanaday" and his ultimate defeat at the hands of his nemesis.

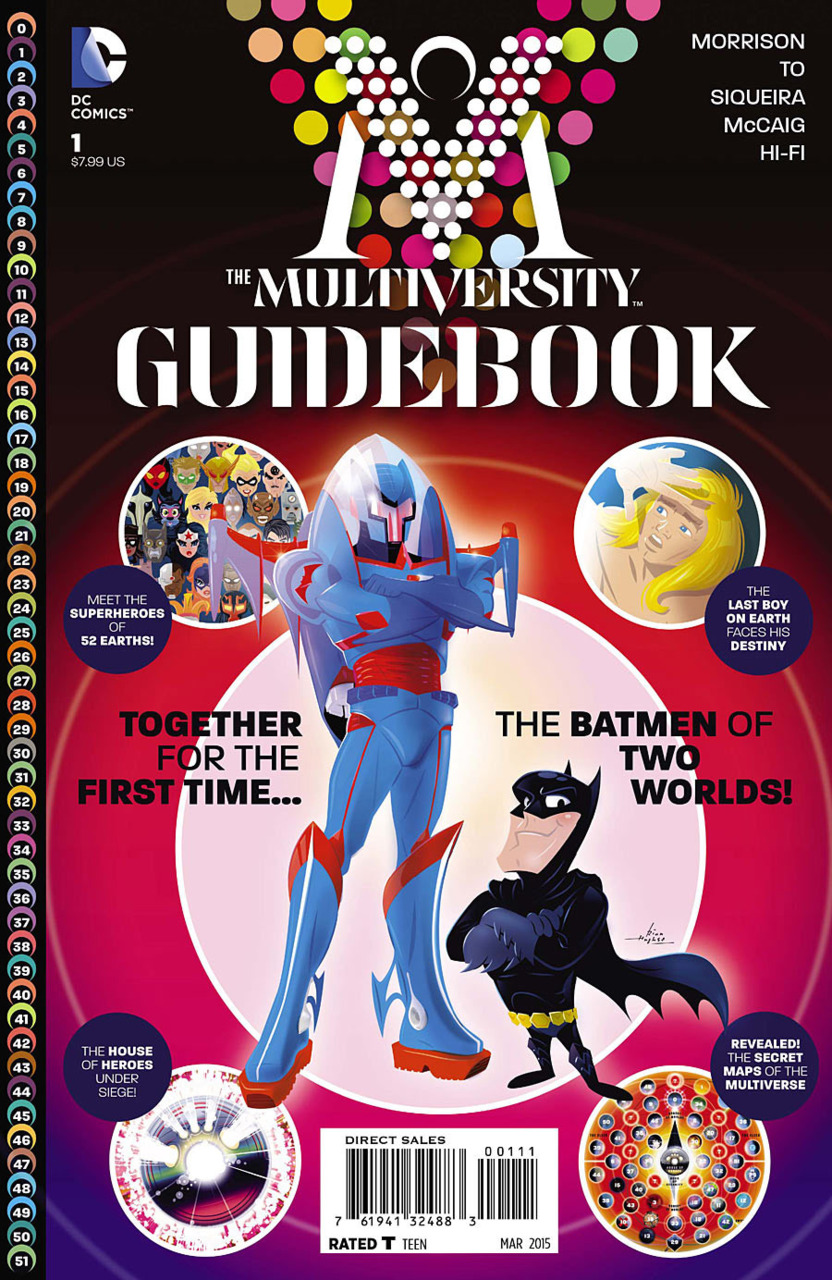

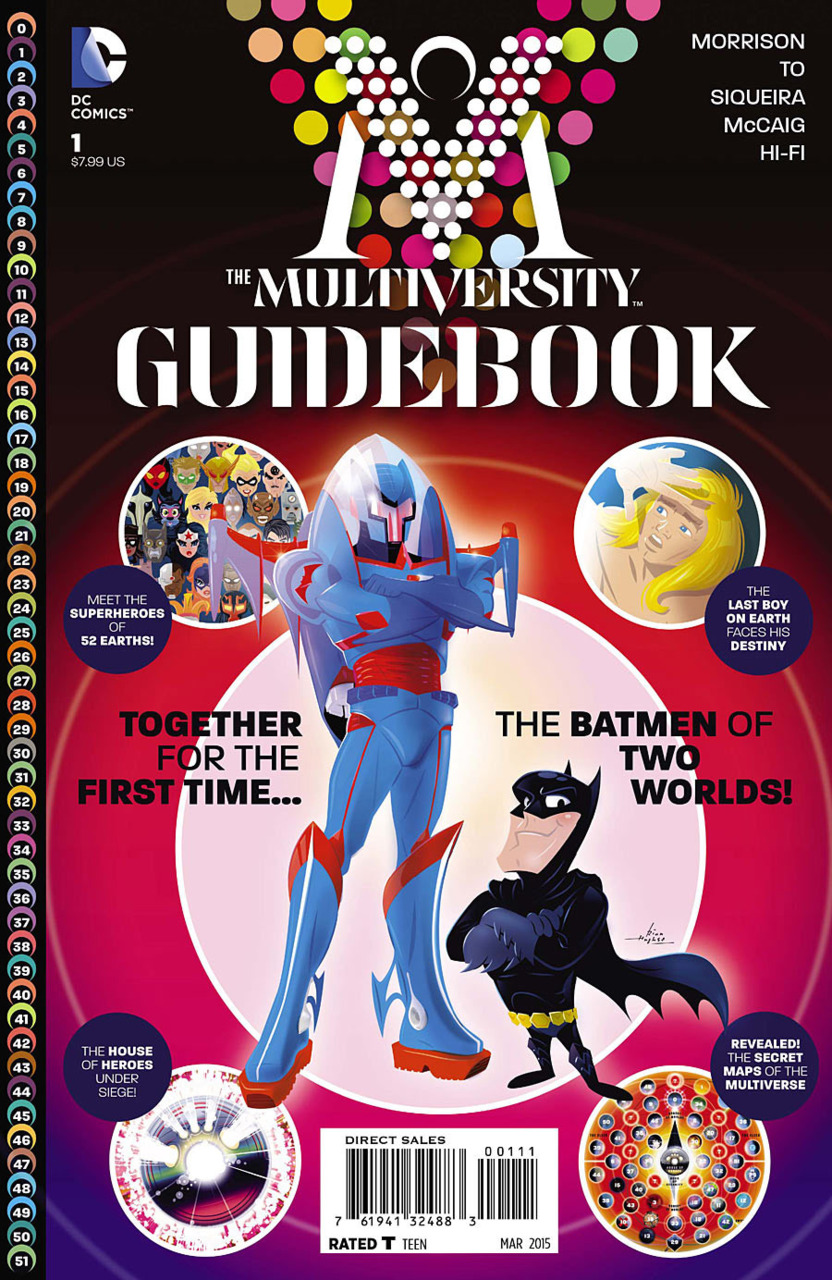

Guidebook:

Maps and Legends

View the Morrison Cover Variant

The sixth chapter, illustrated by various artists, Multiversity Guidebook featured a map showcasing "all known existence", as well a history of the "Crisis" events. The one-shot was published in 80-Page Giant format, in January 2015. It listed 45 out of the 52 alternate Earths within the DC multiverse, while still keeping seven as remaining undisclosed alternate realities. In two companion story sequences, the Batmen of post-apocalyptic Earth 17 and super deformed Earth 42 meet after the League of Sivanas introduced in the previous issue invade Earth 42, slaughtering its inhabitants and metahumans. Earth 17's Batman delays the onslaught from the League of Sivana's robot soldiers so that Earth 42's Batman (Dick Grayson) can get to Earth 17 and relative safety as his world's only surviving hero. Earth 17 Batman arrives at the Hall of Heroes in the centre of the Multiverse. However, the Hall of Heroes is also under attack by the Gentry. On Earth 51, Kamandi and his associates investigate a mysterious tomb that once contained the body of Darkseid, while being observed by the New Gods on New Genesis. The New Gods discuss among themselves that while they are singular entities, their differing "emanations" can live individual existences on different Earths. It is later shown that Nix Uotan is now working alongside the Gentry. As the issue ends, Earth-42's Little League are discovered to be robots—but only Earth 17 Batman is directly aware of this.

View the Morrison Cover Variant

The sixth chapter, illustrated by various artists, Multiversity Guidebook featured a map showcasing "all known existence", as well a history of the "Crisis" events. The one-shot was published in 80-Page Giant format, in January 2015. It listed 45 out of the 52 alternate Earths within the DC multiverse, while still keeping seven as remaining undisclosed alternate realities. In two companion story sequences, the Batmen of post-apocalyptic Earth 17 and super deformed Earth 42 meet after the League of Sivanas introduced in the previous issue invade Earth 42, slaughtering its inhabitants and metahumans. Earth 17's Batman delays the onslaught from the League of Sivana's robot soldiers so that Earth 42's Batman (Dick Grayson) can get to Earth 17 and relative safety as his world's only surviving hero. Earth 17 Batman arrives at the Hall of Heroes in the centre of the Multiverse. However, the Hall of Heroes is also under attack by the Gentry. On Earth 51, Kamandi and his associates investigate a mysterious tomb that once contained the body of Darkseid, while being observed by the New Gods on New Genesis. The New Gods discuss among themselves that while they are singular entities, their differing "emanations" can live individual existences on different Earths. It is later shown that Nix Uotan is now working alongside the Gentry. As the issue ends, Earth-42's Little League are discovered to be robots—but only Earth 17 Batman is directly aware of this.

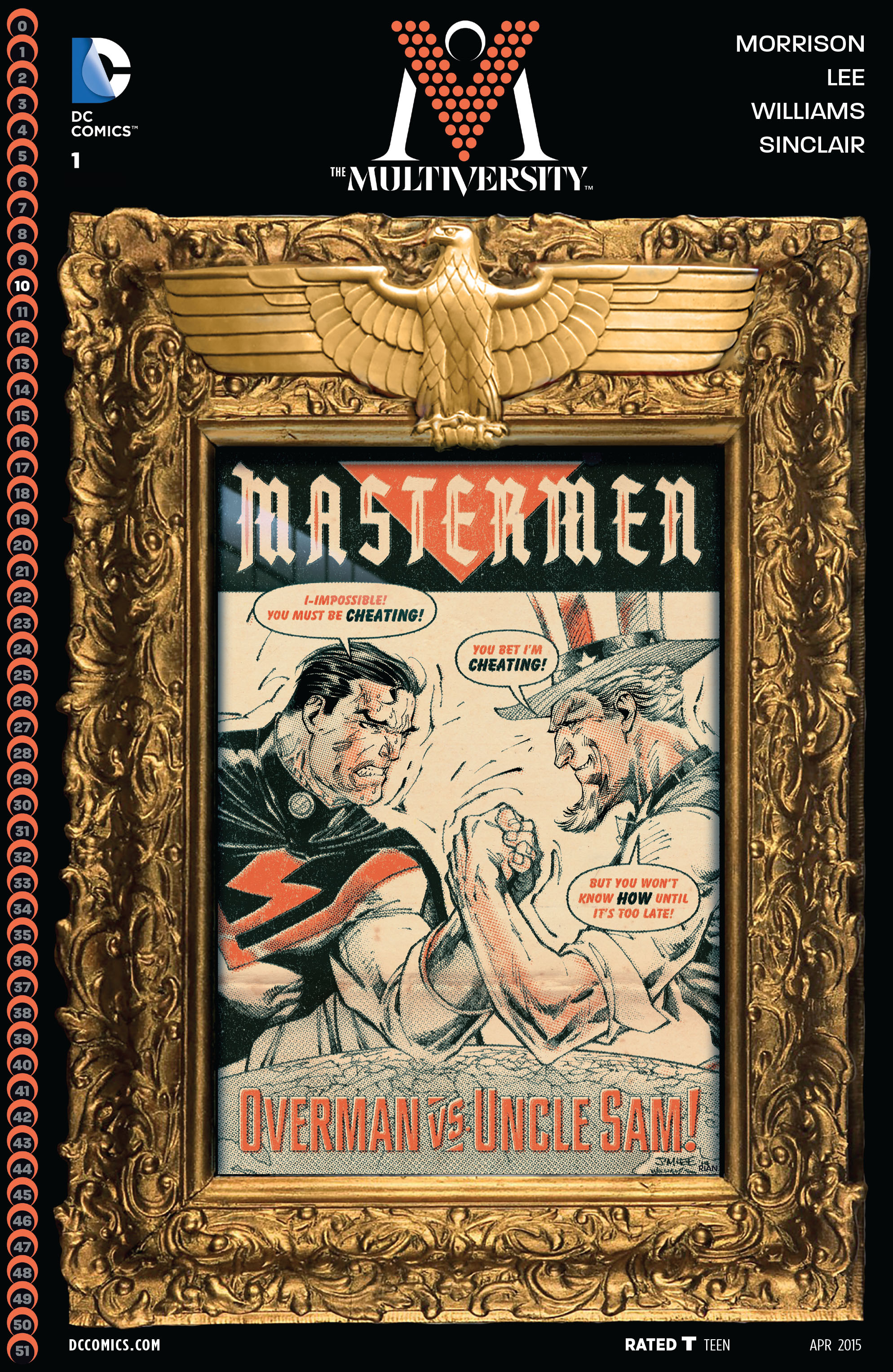

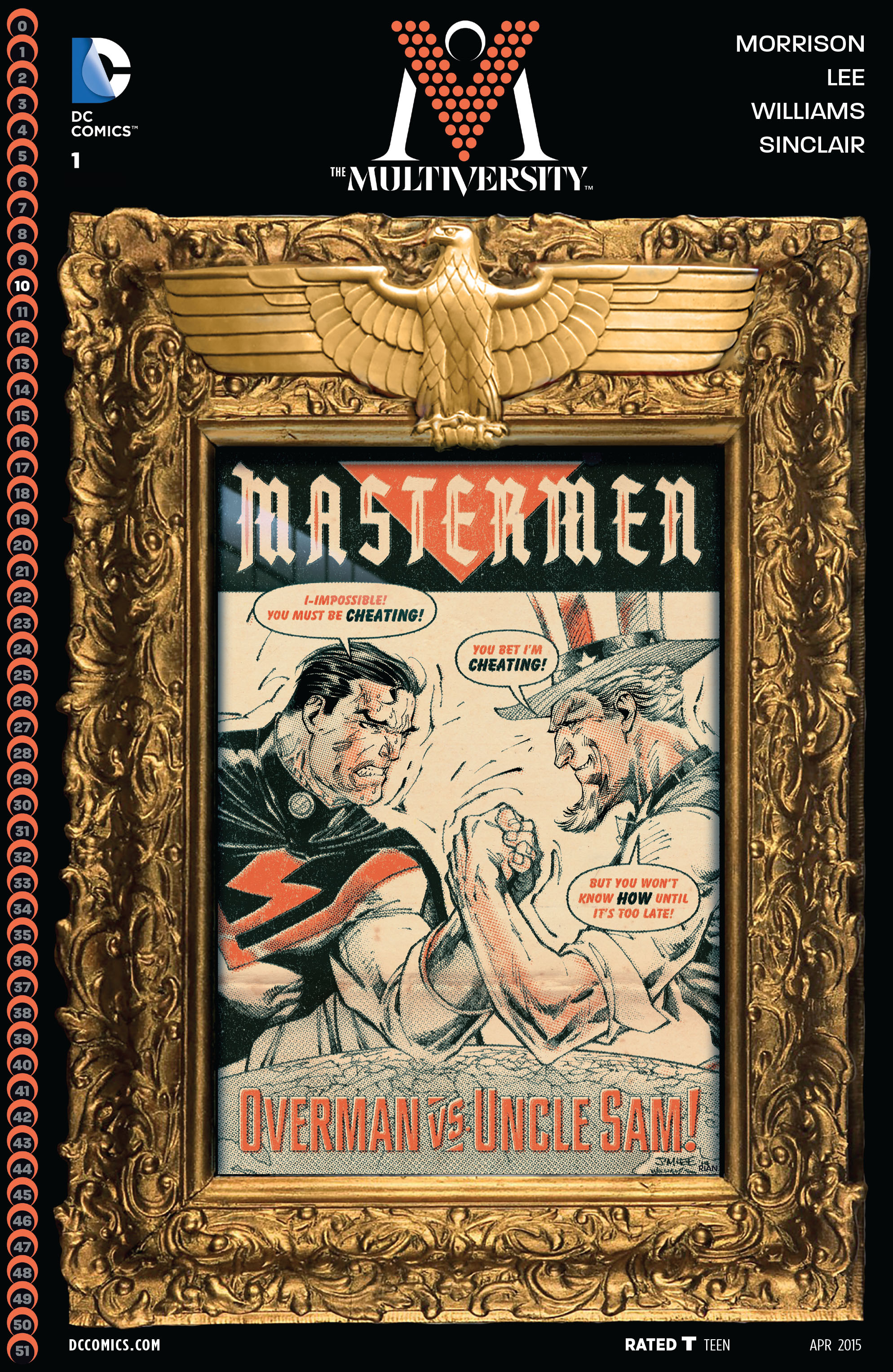

Mastermen:

Splendour Falls

View the Morrison Cover Variant

The seventh chapter, illustrated by Jim Lee and Scott Williams, Mastermen takes place on Earth-10 in 1956, and features characters from Quality Comics as part of the Freedom Fighters and Nazi versions of various heroes. The concept is borrowed from Earth-X, a universe where Nazi Germany won World War II, featured in stories before "Crisis on Infinite Earths". Morrison describes this one-shot as a "big, dark Shakespearean story." The members of this world's Freedom Fighters include a Jewish Phantom Lady, a homosexual Ray, and an African Black Condor, with other members also being representative of groups targeted by the Nazis, such as Doll Man and Doll Woman, who are Jehovah's Witnesses. Overman, the Superman of this world landed on Earth in 1938, in a Nazi territory and was raised by Adolf Hitler. The story is set around a utopia built by this world's Superman after he realizes the evil nature of Hitler, and this Superman "knows his entire society, though it looks utopian, was built on the bones of the dead. Ultimately it's wrong and it must be destroyed."

View the Morrison Cover Variant

The seventh chapter, illustrated by Jim Lee and Scott Williams, Mastermen takes place on Earth-10 in 1956, and features characters from Quality Comics as part of the Freedom Fighters and Nazi versions of various heroes. The concept is borrowed from Earth-X, a universe where Nazi Germany won World War II, featured in stories before "Crisis on Infinite Earths". Morrison describes this one-shot as a "big, dark Shakespearean story." The members of this world's Freedom Fighters include a Jewish Phantom Lady, a homosexual Ray, and an African Black Condor, with other members also being representative of groups targeted by the Nazis, such as Doll Man and Doll Woman, who are Jehovah's Witnesses. Overman, the Superman of this world landed on Earth in 1938, in a Nazi territory and was raised by Adolf Hitler. The story is set around a utopia built by this world's Superman after he realizes the evil nature of Hitler, and this Superman "knows his entire society, though it looks utopian, was built on the bones of the dead. Ultimately it's wrong and it must be destroyed."

In this chapter, Kal-L lands in the contested Sudetenland in 1938 and Adolf Hitler discovers his existence. In April 1956, now Overman, Kal-L presides over the fall of the United States amidst the devastation of Washington DC. Sixty years later, in 2016, an apparently immortal Overman is a member of the New Reichsmen, his world's alternate Justice League, which consists of the Valkyrie Brunnhilde, Underwaterman (an alternate Aquaman), Leatherwing (an alternate Batman, whose parents were Nazi collaborators), Blitzen/Lightning (a female speedster), The Martian (an Earth-10 Martian Manhunter) and unnamed alternate versions of Green Lantern and Red Tornado. His partner Lena seems to be an alternate universe Lana Lang, while Jurgen Olsen, Earth-10's Jimmy Olsen, is his best friend. However, the League of Sivanas is at work in this timeline, albeit unexpectedly on the side of virtue- they are assisting the Freedom Fighters resistance movement. The Human Bomb attacks a memorial to Overgirl in Metropolis and is taken prisoner, held captive within the "Eagles Ayrie", Earth-10's New Reichsmen analogue to the Justice League satellite, where he is tortured by Leatherwing. However, his vulnerability is a facade and he uses his abilities to destroy the Ayrie by damaging its navigation system. It then impacts in Metropolis, killing millions, as well as Leatherwing and Underwaterman of the New Reichsmen. The Freedom Fighters also promise to attack Nazi Germany's lunar and Martian colonies. Although Jurgen Olsen survives, he later discovers the extent of Overman's involvement in the Hitler era and joins the resistance. The destruction of Metropolis is described as the 'beginning of the end' of Nazi Germany in this universe.

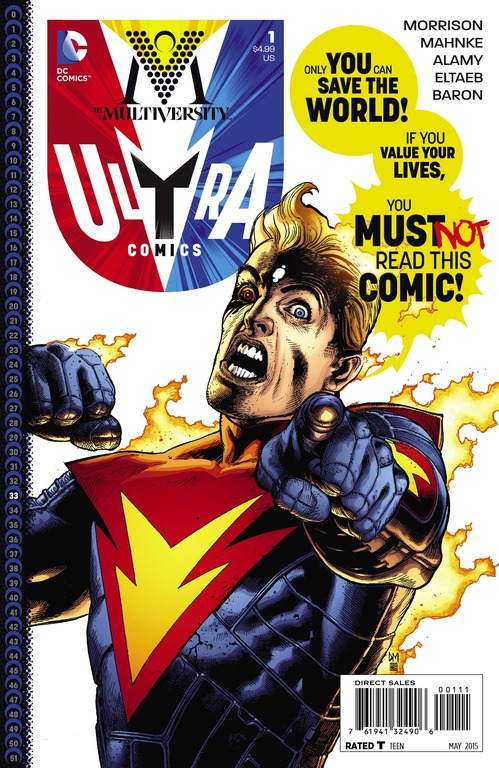

Ultra Comics

View the Morrison Cover Variant

The eighth chapter, illustrated by Doug Mahnke and Christian Alamy, Ultra Comics takes place on Earth-33, a fictional representation of the real world. It features Ultraa, the first superhero of Earth-Prime. Morrison describes this book as "the most advanced thing I've ever done. I'm so excited about this. It's just taking something that used to be done in comics and captions that they don't do anymore and turning it into a technique, a weapon, but beyond that I don't want to say. It's a haunted comic book, actually, it's the most frightening thing anyone will ever read. It's actually haunted—if you read this thing, you'll become possessed."

View the Morrison Cover Variant

The eighth chapter, illustrated by Doug Mahnke and Christian Alamy, Ultra Comics takes place on Earth-33, a fictional representation of the real world. It features Ultraa, the first superhero of Earth-Prime. Morrison describes this book as "the most advanced thing I've ever done. I'm so excited about this. It's just taking something that used to be done in comics and captions that they don't do anymore and turning it into a technique, a weapon, but beyond that I don't want to say. It's a haunted comic book, actually, it's the most frightening thing anyone will ever read. It's actually haunted—if you read this thing, you'll become possessed."

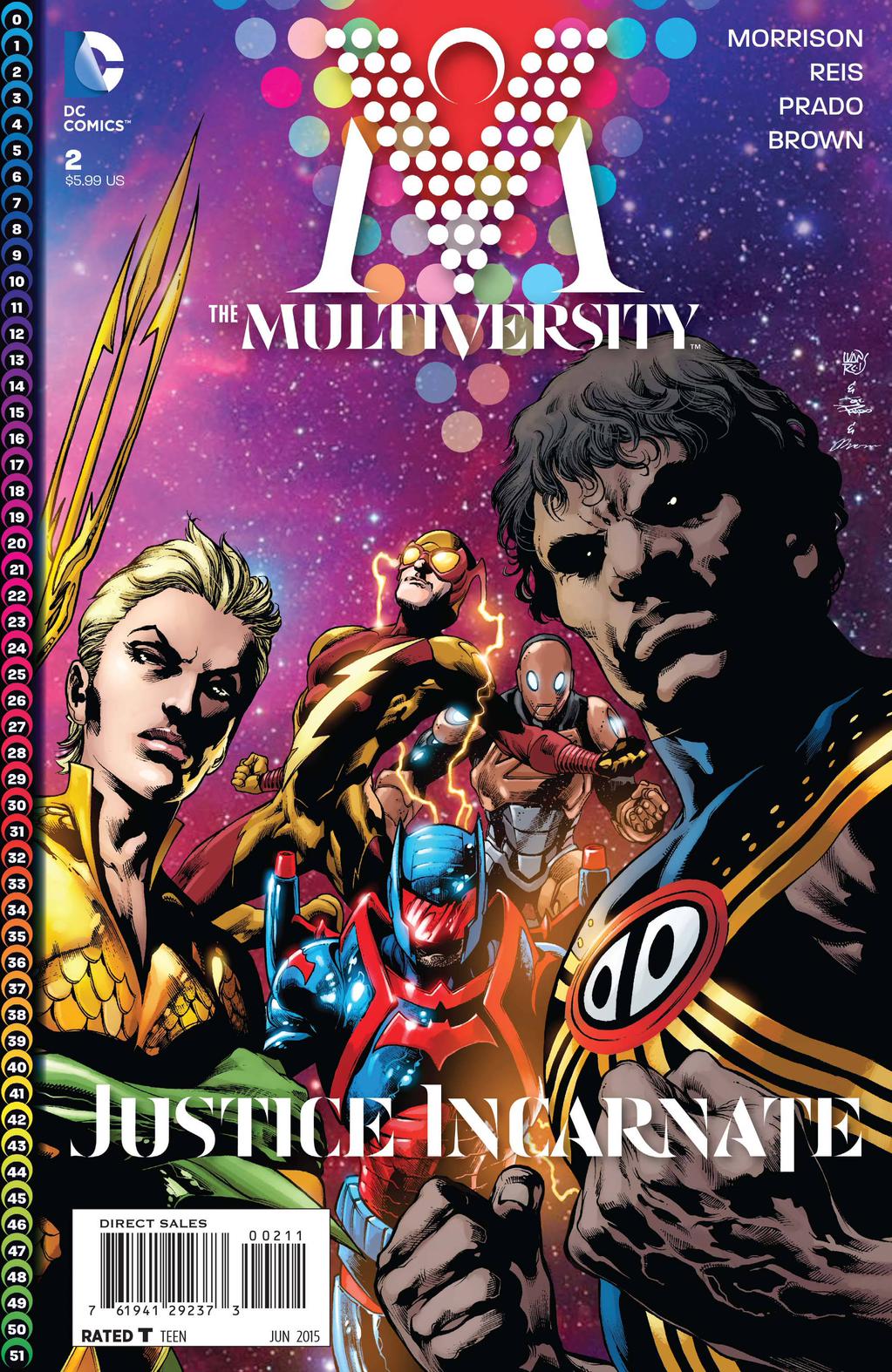

The Multiversity #2:

Justice Incarnate

View the Morrison Cover Variant

The ninth and final chapter, illustrated by Ivan Reis and Joe Prado, The Multiversity #2 features the final battle against the Gentry, as well as featuring the League of Shadows (an alternate Justice League) from the magically inclined Earth-13. With the assistance of the "Blood League" (vampire Justice League analogues) of Earth-43, Vampire Sivana launches a covert invasion of the twilight-shrouded supernatural Earth-13, but reckons without the opposition of Superdemon Etrigan and his "League of Shadows" (supernatural metahuman coalition) on that world. At the Hall of Heroes, the Harbinger AI reboots and sends out a distress call for reinforcements across the Multiverse. Much of the action in this final issue occurs on embattled Earth-8 and centres on Nix Uotan, the renegade ex-Monitor, as Earth-23 Superman, Earth-11 Aquawoman and Captain Carrot of Earth-26 combat him as he tries to resolve a rubiks cube device that will trigger the arrival of the Gentry on that world and its prospective destruction. Earth-36's Red Racer calls on assistance from the Multiverse's other speedsters, while Earth-17's Batman uses the Multiversity Guidebook as antiviral software against Hellmachine's hacker attack against the Harbinger AI, enabling the latter to eject the hapless Gentry, leading to its death. Meanwhile, an alien fleet is invading post-apocalyptic Earth-17, Justice 9 fights a zombie Optiman on their native Earth-36, the Society of Super Heroes witness the revival of a Mayan Nix Uotan idol on Earth 20, startled metahumans witness events around them on Earth-48 and the Zoo Crew face off against the Justa Lot of Animals team on Earth-26 as conflict spreads through the Multiverse. Captain Carrot is temporarily decapitated but his cartoon physiology enables him to survive until Red Racer can feed him a cosmic carrot and reattach his head. Freed, Harbinger rallies other metahumans across the Multiverse and uses transmatter cubes to channel them to Earth-8 as Nic Uotan is exorcised of anti-Multiverse influences. With such overwhelming numbers, Intellectron, Dame Merciless and Mr Broken are defeated, leading to a final if inconclusive confrontation with the satanoid leader of the Gentry on Earth-7. Any future conflict is postponed, but one of the consequences of the event is a multiverse-scale Justice League, entitled "Justice Incarnate."

View the Morrison Cover Variant

The ninth and final chapter, illustrated by Ivan Reis and Joe Prado, The Multiversity #2 features the final battle against the Gentry, as well as featuring the League of Shadows (an alternate Justice League) from the magically inclined Earth-13. With the assistance of the "Blood League" (vampire Justice League analogues) of Earth-43, Vampire Sivana launches a covert invasion of the twilight-shrouded supernatural Earth-13, but reckons without the opposition of Superdemon Etrigan and his "League of Shadows" (supernatural metahuman coalition) on that world. At the Hall of Heroes, the Harbinger AI reboots and sends out a distress call for reinforcements across the Multiverse. Much of the action in this final issue occurs on embattled Earth-8 and centres on Nix Uotan, the renegade ex-Monitor, as Earth-23 Superman, Earth-11 Aquawoman and Captain Carrot of Earth-26 combat him as he tries to resolve a rubiks cube device that will trigger the arrival of the Gentry on that world and its prospective destruction. Earth-36's Red Racer calls on assistance from the Multiverse's other speedsters, while Earth-17's Batman uses the Multiversity Guidebook as antiviral software against Hellmachine's hacker attack against the Harbinger AI, enabling the latter to eject the hapless Gentry, leading to its death. Meanwhile, an alien fleet is invading post-apocalyptic Earth-17, Justice 9 fights a zombie Optiman on their native Earth-36, the Society of Super Heroes witness the revival of a Mayan Nix Uotan idol on Earth 20, startled metahumans witness events around them on Earth-48 and the Zoo Crew face off against the Justa Lot of Animals team on Earth-26 as conflict spreads through the Multiverse. Captain Carrot is temporarily decapitated but his cartoon physiology enables him to survive until Red Racer can feed him a cosmic carrot and reattach his head. Freed, Harbinger rallies other metahumans across the Multiverse and uses transmatter cubes to channel them to Earth-8 as Nic Uotan is exorcised of anti-Multiverse influences. With such overwhelming numbers, Intellectron, Dame Merciless and Mr Broken are defeated, leading to a final if inconclusive confrontation with the satanoid leader of the Gentry on Earth-7. Any future conflict is postponed, but one of the consequences of the event is a multiverse-scale Justice League, entitled "Justice Incarnate."

Digging Deep Into The Multiversity With Grant Morrison

This is Matt D. Wilson's article at Comics Alliance.

Comics Alliance: We had talked about Multiversity a little bit at Comic Con, and things have crystallized a lot more now that five issues of the series are out. One thing I've seen a lot of people talk about in having read these five issues is that you kind of threw us into the deep end on this thing. The latest book to come out is the Guidebook, which one would suspect is going to give a little additional clarity to the series.

Why did you decide that the Guidebook was the sixth installment? Why throw us into the deep end right at the beginning?

Grant Morrison: Well basically, honestly, everything is based on my first experience with superhero comics. One of things I remember picking up was the Justice League #45 — I think it's 45 — and that the Justice League is fighting Antimatter Man. It's a team-up with the Justice League and Justice Society.

I had never seen Justice Society in my life, you know, but suddenly there are all these fabulous characters, Dr. Fate, Star Man. All these beautiful designs I've never seen before and I knew nothing about them, but just reading that comic with absolutely… as you say, thrown into the deep end of the super hero universe. I was utterly captivated. And pretty much every comic I've loved has been like that.

I think people come to comics and they never come with a guidebook unless, they're more prepared than we are and they've already studied the whole thing. Most people discover comics, you know, someone lends you a book and you really get involved in it, and you really like it. Or you find one or pick one up just on the off chance and get involved, you know.

It's the same as when I got into the X-Men. I came in right in the middle of what Chris Claremont and John Byrne were doing. I was so utterly blown away by it that I had to find more. So I guess all my work is trying to recreate that feeling of almost chaotic immersion in something that's much bigger than you and has been around for a long time and just leaves you excited and filled with tension

Based on that, you know, as you say, I like throwing people in and letting them sink or swim, because I think most people who read comics, if you enjoy them at all, then you'll like it, and you'll start swimming. That's why the guidebook comes later. I do want to explain all that stuff, and I do want to systematize a lot of these things, but at the same time, I just want to create that mad rush of just discovering comic book universes for the first time, to just throw in and learn who the characters are. Being able to go online as you do nowadays and check on things makes a lot easier than when I was a kid trying to figure out who the hell Dr. Fate was.

So it's really about that, you know. I just want to create the experience. That mad, crazy, rush of discovering all these characters. The guidebook comes in halfway through so that if you're really getting too exhausted, then you get an explanation of pretty much everything.

CA: There are little bits and pieces throughout these issues of Multiversity – particularly in New Thunderworld Adventures — clues as to what some of the universes we're not seeing in an entire issue are. Take for example Luchador Dr Sivana, who I'm extremely curious about. I'd love to read more about him. Is the idea of putting those little seeds in these issues kind of a way to, maybe open the door for more creative teams or writers to pick up the baton on some of these universes you're not exploring in depth in particular issues and run with them?

GM: Oh, yeah. Again, that's one of the things about these ongoing, long-running universes of DC and Marvel, particularly DC, because it's my favorite. To me, that's what it's all about. You pick up a little piece of something, you know, pick up a little piece of a Gardner Fox story and turn it into a brilliant Green Lantern short or what Geoff Johns does when he finds an obscure character [and flesh him or her out], because all these things are left lying about, and the great thing about superhero universes is they don't really end, and the story never really ends.

It's always a crisis, and again, that's a lot of what Multiversity is ultimately about. It's the fact that there is no end to these stories, and that's what makes them great to a certain extent and we can throw in a character or a hero or a villain that's only in a few panels but may inspire another creator to create an award winning six-issue mini-series or whatever. So, it's very much that. It's what I love about them, is the open-ended nature and the sprawling kind of epic, no-horizon nature of these stories.

CA: The issue in Multiversity that has maybe generated the most discussion is Pax Americana, so let's talk about it. There's a scene in there where Captain Atom is looking at his dog and trying to figure it out, and in the process of such, takes the dog apart and realizes that he's killed him.

There's a certain reading of that which you can take to mean that deconstructing something that you like is ultimately destructive. Is that the point you're trying to make there? Trying to dissect a comic like this too much takes away some of the enjoyment?

GM: Yeah, but you'll notice I did it in a comic that was deliberately designed to be dissected [laughs].

It's very much drawing attention to that. The techniques in there are so in-your-face. It was really gratifying to see the amount of effort people put into working out stuff in Pax. I really appreciated that.

But at the same time, I attempt to do that with pretty much everything I write. I don't telegraph it as much. The final year of Batman Incorporated was as tight, controlled and as wound around its seams as Pax, but I didn't signal every way I was doing it. With Pax, I signaled it so I was forcing people to dissect, and then I confronted them with the dog scene.

I'm one of the people that loves to dissect stuff. I love to get into the meanings. I love breaking it down. But I'm sure you're like me. We all know those moments when we're sitting with friends, and we're really enthusiastic about something we all love, and we keep wanting to talk about it. We keep wanting to get further and deeper, and there comes a moment where you go, all we're left with is the pieces here [laughs]. It doesn't seem very palatable anymore. I think there's an inescapable thing when you do dissect something down, the dissection is always done from a point of enthusiasm and excitement or a need to engage with something a lot more. What you're doing in a lot of cases is ending up with something dead in your hands.

As I said, I'm not doing this as a moralist. I'm just pointing out that this happens. I'm pointing this out in a comic where a comic critic is the main character, in the form of Nix Uotan. It's just making a point, but not necessarily so people should stop doing this, because I can't stop doing it. I'm sure there are people who like things — they like TV shows, they like comics, they like books — who'll continue to do it, but there is the horrible fact that at the end, we're usually left with something dead and stuck in a museum case and no longer giving off the same vibe of life and excitement and potential that it did when you first picked it up.

CA: It's impossible to ignore the similarities, structurally and in the characters and everything else, between Pax Americana and Watchmen. I know that you've written previously about your take on Watchmen in Supergods, where you wrote — and forgive me if I'm putting words in your mouth — that you saw it as an exercise in form, maybe as a little too confined by that form. How did that play into Pax Americana, and particularly the notion that life is comics?

GM: Where to start? [laughs]

It's meant to be like Watchmen in the way that the The Rutles are like The Beatles. There's no sidestepping it. That's what it's about. It's about Watchmen. It's about that type of storytelling. It's about the very tight, closed, controlled universe that's created for something like Watchmen. All the tricks we use with design make you feel quite pressurized and enclosed.

I think some of the things that people missed — I read a lot what people think about how the president's a good guy, hunting for the hero in this story — but there are no heroes in Pax Americana. The president is a delusional murderer who killed his father, although quite inadvertently, and now he wants to commit suicide. Most of the superheroes have got serious problems of their own. So one thing people shouldn't imagine is that there was a good guy in Pax, and the president's plan might lead to anything other than disaster.

That's one of the things I took from Watchmen, is the sense that there is no moral sense, except in Watchmen there's a moral sense of the slightly repugnant, yet lovable Rorschach. We didn't even want that much of a moral sense. I wanted it to be more like the real world. It seems like the real world, but when you actually look at it, you realize that the Gentry characters, the bad characters, might have trouble penetrating this world, although it seems like that world has a lot of problems.

In actual fact, it's super-tight. That's what the president intuits when he has his moment of revelation. It's the structure of the comic book universe that he's in, which is controlled by eight-panel grids. He's actually realizing that he's inside something that is structured and is crystallized, and it does have reasons and meanings, but he doesn't necessarily know what the reasons and meanings are, because he's slightly deranged.

It was very much about what was it like to be trapped in a story with you're utterly under the control of the author, and every single thing you do has to tie into a grid, and how that may reflect on the inhabitants of that universe. So Watchmen was a very useful tool to then go back and use that on the characters which were part of the original inspiration for Watchmen. It just seemed funny to put them in a Watchmen-style story.

The fact is, with Pax I kind of figured out an entire season of stuff that no one will ever see. So it was all there. As a critique of Watchmen, I think the critique is there was well. The narrative techniques and the formal devices are so in-your-face it's practically like setting off fireworks, isn't it? It's almost an affront to critics, I would think, because it's so in-your-face. But I guess that also makes it easier to pick at.

One of my critiques of Watchmen is that I feel that the formulaic devices, while they fascinate me, and they do fascinate me because they're so perfectly deployed. There's not a line out of place in it. But in the service of trying to talk about reality, I don't think reality is like that. As the president himself says when they're walking through the gardens of Captain Atom, “These gardens are a masterpiece of design and organization. Life, by contrast, seems a puzzle, a maze of contradictions.”

To try and suggest real life by using intense formulas is, to me, a kind of dead end. So, if there's a critique at all, that's the critique. But otherwise, I also want to honor Watchmen, which is an amazing artistic achievement, by doing something that's at least trying as hard as Watchmen to pack the panels with meaning and connection.

CA: One of the thematic elements that goes throughout Multiversity is what you might call the destructive nature of knowledge. You talk about President Harley being deranged. Nix Uotan gets a certain degree of knowledge and becomes a monster because of it. Captain Atom just leaves the universe when he reads Ultra Comics. Algorithm 8 is something that exists. It's almost this Lovecraftian idea that the knowledge of your existence drives you mad.

GM: Slightly, yeah. I think the main idea in Multiversity, what I wanted to talk about and what all the books are about, but particular the Ultra Comics issue and the final issue, is quite simply: Be careful what you let into your head.

In a world where everything is protected — people live in houses with locked doors, they put their valuables in safes, they keep their information safe behind passwords and antiviral controls — we allow pretty much anything into our heads. Particularly since the Internet age has really got its teeth in and we're starting to see some of the effects it's having on people.

I think, to some extent, that's a glut of information and a tide of information that's almost too much for people to take. It has resulted in a kind of sickness in people, exhaustion or resignation. So, ultimately Multiversity is about that, because I like to write stories about stuff that I'm seeing in the world around me, or the stuff I'm feeling. It's about, are you sure you should be letting all this stuff into your head? How do you honestly feel about all the porn and all the things you see, all the beheadings? What's it doing in there?

The Gentry kind of represent all those things that we just accept. To me, the result I'm actually seeing is a kind of soul weariness, a cynicism, a sickness that permeates culture. I think we're all fed up with ourselves and we're just waiting to be destroyed by the other.

CA: You've mentioned the Gentry a few times and we saw them in their clearest form in the first issue, Multiversity #1, where they announced themselves. Since then, they've only shown up in ways you sort of have to just guess that they're there. With that in mind, and given that we've got a handful of issues left before this wraps up, it's sort of hard for me to wrap my head around the notion that all of this can be tied up in a bow in one, big wrap-up issue.

GM: That's how I feel every time. [laughs]

CA: How much of a challenge was that to put together, first of all, and is the ending we're going to be more of a symbolic ending? Or do you really expect the ending to be more of a concrete, “Here's what happens with the Hall of Heroes and Nix Uotan, and here's what happened in all these universes”?

GM: Pretty much. We don't get into all the universes. You certainly get, “Here's what happened.” All the main characters that have been introduced so far, with Red Racer and all those people from the first issue, all get their moments and get their stories taken to the conclusion.

So yeah, it's there. There are kind of three endings, and the final ending is probably one of the most concrete things about the whole series. It becomes very down-to-earth and very street-level on the last page. I do want to make it work on that level. Most of these things, they do work on that level. I think they always do. As these things are coming out, it's just the shock of the new that seems to freak people out.

Final Crisis has suddenly become a book everyone can understand. There were people who were forming camps to fight about it. I think people tend to approach my work thinking it's lot more complex than it is, but most of it's on the page, and most of it's an attempt to talk to other comics readers about the stuff we're into. Particularly these superhero comics, they're quite hermetic in that sense, in that there are so many other comic writers and so many other people who read comics get excited by them, criticize them or critique them.

At the same time, I'm trying to talk about real things. That's where the symbolic content comes in, where the Gentry represent all these bad influences, but really each one of the Gentry is kind of a villain archetype taken to the limit. Intellectron is the mastermind taken to the limit. Dame Merciless is the femme fatale taken to the demonic limit. Demogorgunn is the zombie horde taken to the limit, and so on through the rest of them. Lord Broken is the madhouse, Arkham Asylum taken it to the limit. Each of them represents a fairly understandable villain type once you think about it.

So the symbolism becomes, well what do they represent in the real world? For me, they represent forces of nihilism and anti-human hatred, ignorance and greed and stupidity that I see every day. Those aspects of the story, how do you deal with those? How do you communicate those? What happens when there are too many of them in your head and you're starting to feel sick with it? That's the symbolic element in the comic, but at the same time I still have to show what happens with Red Racer's affair with Flashlight [laughs]. I still have to show what happens to President Superman at the end and make sure everyone gets returned to their homes and all the crises are brought to an end satisfactorily.

CA: The term “The Gentry,” between myself and my friends and then other people who over-analyze this stuff sometimes, we've talked about the term and where that could come from and what that can mean. A lot of times those conversations come back to the idea of gentrification.

GM: Yeah, absolutely.

CA: This idea of a force or a group of people coming into a community and then changing it. Is that part of the idea? That there's this evil faction that seemingly comes from genres outside superheroes and are invading these comic universes?

GM: The great thing about broad symbols like this is you can interpret them in different ways. For me, the name The Gentry initially came from — it was one of those words that people used to use in order to not to talk to the seelie people, the other ones, the strange ones from the dome. Back in the day, they had all these names, the good people or whatever, the “tripping darlings.” All these strange epithets that people would use rather than mention the seelie by name.

The Gentry was one of those names and it just stuck with me when I was thinking about beings from beyond, and we used to call them The Gentry. Then I thought of them as being bad things from beyond. From that, they started to grow, and then as you said, this idea of gentrification. When I'm talking to you about the kind of ideas we let into our heads, and taken as a thesis of, what if we let in so many shitty, shoddy ideas that we have completely ruined the neighborhood in there? We've dismantled, we've wrecked our inner houses and we've destroyed our inner palaces, and we've placed crackhouses in there, imaginatively.

I don't necessarily believe that this is all true. I thought it would make an interesting idea for a story, so the Gentry then are these bad ideas that come in you when you've messed up your head [laughs], so they come in and start rebuilding because you've now made it comfortable for them to recreate and build in their own image. So that, again, that's one of the big things it's about, this notion of gentrification coming into places and places that have been seemingly broken down and left to ruin and then rebuilding for them the benefit of your own kind.

CA: I love how you jump around between different genres, but since The Multiversity is one big story, what I'd like to know is, in a few months, when this thing is completely finished, and we've read it all, are we going to go back into some of these issues that seem to be self-contained stories and a light bulb is going to go on where we see how it all connected?

GM: I hope so. I hope the presence of The Gentry will be more clear. For instance, in the Captain Marvel comic we have dozens and dozens of Sivanas, so they can represent Demogorgunn, as they always appear as some kind of horde. Or Demogorgunn could be the zombies in issue #2 or the Superman robots in issue #3. Because they're demons, they come in different forms in each world, so I do hope when it's finished, yeah, you should be able to look back and find a lot of new stuff and hopefully, that's way it's been built.

Even to notice that certain things, like the Thunderworld comic that seems quite sweet and light isn't, actually. [laughs] There's a lot going on, a lot of weird things going on under the surface of how the characters are presented and portrayed. I think it'll make it slightly more interesting to go back when we've seen everything.

CA: In the issue The Just, there's the painting of “the creepy lady.” That seems like the most obvious Gentry appearance to me. But there's also all these other things to chew on, like the number eight appearing so much.

GM: There's this idea of octaves and music, because of DC's Multiverse, at least, is based on vibrations and tones, and it seems like an interesting thing to do, to base everything around a Western musical scale.

CA: There's a pretty clear tie to Final Crisis in issue #1, with Superman singing or playing a song to save the universe.

GM: A lot of people just thought, where the hell did this come from? To me, I think this is the prime basis of the DC Universe, that it's made of vibrations, so if you want to change anything then you have to change it with a simple song. Most people thought it was insane when Superman sings and saves the day, but for me, it came from the very root of how the DC Universe is.

Grant Morrison Unleashes a Haunted Comic in The Multiversity: Ultra Comics #1

This is Sean Edgar's article at Paste Magazine.

Paste: So in this issue we've finally come full circle in the The Multiversity project, with the cursed comic shown in the first chapter, Multiversity #1. This comic is referred to as being infected and haunted. What makes it so?

Grant Morrison: There's a very bad idea hidden inside the comic book, and the bad idea will be revealed if you continue to read it, so you may not want to know this. The bad idea is ultimately not that you stop reading the story, but the story dies, which by implication means that you one day will also die. The new horror that's revealed is the Oblivion Machine in Ultra Comics; consuming comics is devouring the hours and the minutes of your lives, and you're actually being vampirized by your entertainment media. That's the ghost in Ultra Comics, that you're being devoured by the story that you're consuming, because you could be out there meeting the girl of your dreams or flying out a microlight. It's about the things that we consume, the pictures that we love to watch.

Paste: After reading it a few times, the comic operates on a perpetual loop—the beginning is the end is the beginning. Without being too ambiguous, is it meant to have a resolution or does it function more as a disquieting rhetorical question?

Morrison: I think the questions are kind of answered if you read it multiple times. It's meant to be like a loop. It's meant to be like you're trapped inside with something malevolent. And how you figure out what you've been told by the malevolent entity, it's kind of down to the individual reader. Quite literally, everyone who reads Ultra Comics will be connected across time and space by the fact that they're reading Ultra Comics. The comic is a gigantic node of a network. Even when I'm dead, people might pick up a back issue of Ultra Comics and be part of the story again. Every mind that becomes part of Ultra Comics becomes part of this superhero network. The idea was how closely could we embed a fictional entity into the real world and connect it to real people, and enter real people into what we were doing.

Unlike all other earths in the multiverse, [Earth-Prime—our earth where this issue takes place] doesn't have superheroes. What we have are representations. Without movies, without comics, what would a real super hero be like in our world? Maybe it would be a giant network of minds all connected by reading the same experience, ultimately in the same place, in the same room, at the same time, no matter how far apart they are geographically or historically.

Paste: This issue takes place on Earth-Prime, our own earth, and speaks directly to comic books and their pragmatic effect on readers. In your decades as a creator, do you think comic books have assumed a different relationship in how they effect their readers? One of the most interesting twists here is how online commentary plays into a battle with The Gentry.

Morrison: Yeah. Something very interesting has happened since the dawn of the internet in the sense that the audience can respond immediately, and everything becomes almost like a live performance. And no matter how much we say we don't care about this stuff and we don't read this stuff, of course we look at it. It's influencing everything. I think the dialogue between the creators or the authors and the consumers is now so tight and so close, that it has to be acknowledged as a major part of the experience of creating pop culture in the 21st century. And again, I wanted this comic to go there because I think it's a fertile field. Nobody's really talked about it and how we all respond. We listen to what they're saying, we adapt to stances, we change and they change. Everyone playing this strange game has to be acknowledged at least in a work like this one, particularly, which is about that relationship.

Paste: On that note on community, I've seen a lot the style you cemented for Vertigo in the ‘80s trickle down to this generation. When I saw the Neighborhood Guard, the first thing I thought was Farel Dalrymple's The Wrenchies.

Morrison: I haven't seen that one either because I live out in the country, and I never see any bloody comics except the ones that DC sends me. But I've read about it. I was thinking of it more like the Jack Kirby kid gangs. It's almost 1940s or 1930s stuff to be honest. Because Ultra is about pop culture and kind of where we are now, with these representations of dystopia and apocalypse and the end of civilization. So I wanted the Neighborhood Guard to represent that. They're still hopeful, they're still plucky young teenagers of the actual new world to be confronted with constant, miserable news every day of their lives.

Paste: Multiversity is just so big and massive in scope, panning out to dissect how the realities between comic fiction and the world intersect. It's also a theme playing out in Annihilator, albeit as a reflection on the film industry. This project feels so definitive and absolute; are there more meta comic events that you could write past this? Am I being unimaginative by asking where do you go from here?

Morrison: I realize it's my master theme. A lot of times I'll be working on a thing, and I'll be thinking here's another story where a person wakes up to the true nature of reality and I'll think, ‘Grant, come on—why do you keep doing this?' But it is the thing I'm most interested in and is most useful to the way we live now, in this hyper-accelerated, digital media sphere. The difference between who we are and what we try to be is so ridiculous. So I'm embracing it, in the way that Philip K. Dick always wrote stories about people taken into the world that exists underneath reality, I think that's just my master theme and my master goal. Annihilator's got a little bit of that; it's not everyone living in the same simulation, but all of my characters are living in a world that isn't quite the real world. And the stories are all about them discovering what the real world is. There are a couple more to come, and maybe I'll break the cycle.

Paste: What might those stories be?

Morrison: I've got a few creator-owned projects coming out, like Sinatoro and the conclusion of Nameless, which go to similar places in a different way. But beyond that as I tell everyone, the big influence is the Wonder Woman: Earth One book I've been doing for the last couple of years with Yanick Paquette, and we're almost finished. That changed the entire playing field for me. I wrote a book that wasn't reliant on the structure of boys adventure fiction. It opened up a whole new way of looking at things. Beyond Wonder Woman, I think there may be some very different ways of thinking about things.

Paste: The Multiversity #2 comes out next month, concluding the story. I think The Gentry has been my favorite aspect of the book—I know each member is an extreme of various villain archetypes, but they also seem to represent something so much more primal. Are we going to discover more about these characters and what separates them from a character like Darkseid?

Morrison: Oh yeah, you definitely find out a lot more about them, but at the same time I think why they work is because everyone can read them in their own way, and make them represent what they want them to represent. I want to keep that little bit of mystery. The finale pretty much explains who they are, and even in Ultra it's explained that these are really bad ideas. They're demon ideas and we incubate them and they form. We can feel them, but we don't quite know how to display them and what they're doing. It's been portrayed that our imaginative space has become degraded. Where once we had Star Trek now we have The Walking Dead. We see our civilization as something that's basically, ultimately doomed. And maybe a generation ago we saw our civilization as something that would naturally be carried into the stars, and have this fantastic utopian future. So Multiverse is all about that, and Ultra is specifically about the idea that we have impoverished a neighborhood, and once you've impoverished a neighborhood then you come in to gentrify it. You've made it very comfortable for the monsters to cultivate.

Paste: Is there anything else you'd like to add at all?

Morrison: One more thing is that Ultra Comics was inspired by the 1970s head comics. I don't know if you've ever read Jim Starlin's Warlock or Captain Marvel. I grew up on that. Back in the day, people like Starlin would come back from Vietnam and did these fantastic allegorical kind of Pilgrim's Progress-style superhero comics. So I think Ultra Comics was my and Doug Mahnke's attempt to almost create one of those cosmic comics of the ‘70s. Everything is allegorical. Everything is a metaphor. Everything is some psychological state. I will mention that, because those guys were a big inspiration for this particular issue.

|

|